By: Izzy Cheung, Arts & Culture Editor

My dad was born in Kowloon, Hong Kong. He came to Vancouver in 1974 and has lived here ever since. But, when he boarded the plane to BC, he brought many Hong Kong traditions along with him. As a kid, I remember watching my dad return from long work days carrying little tetra-packs of Vitasoy — specifically the malted ones. The wrappers of White Rabbit candies were sprinkled around my grandma’s house like grass on a lawn. And, while I never particularly liked the texture, jook 粥 (congee) was always a household staple when any of us got sick.

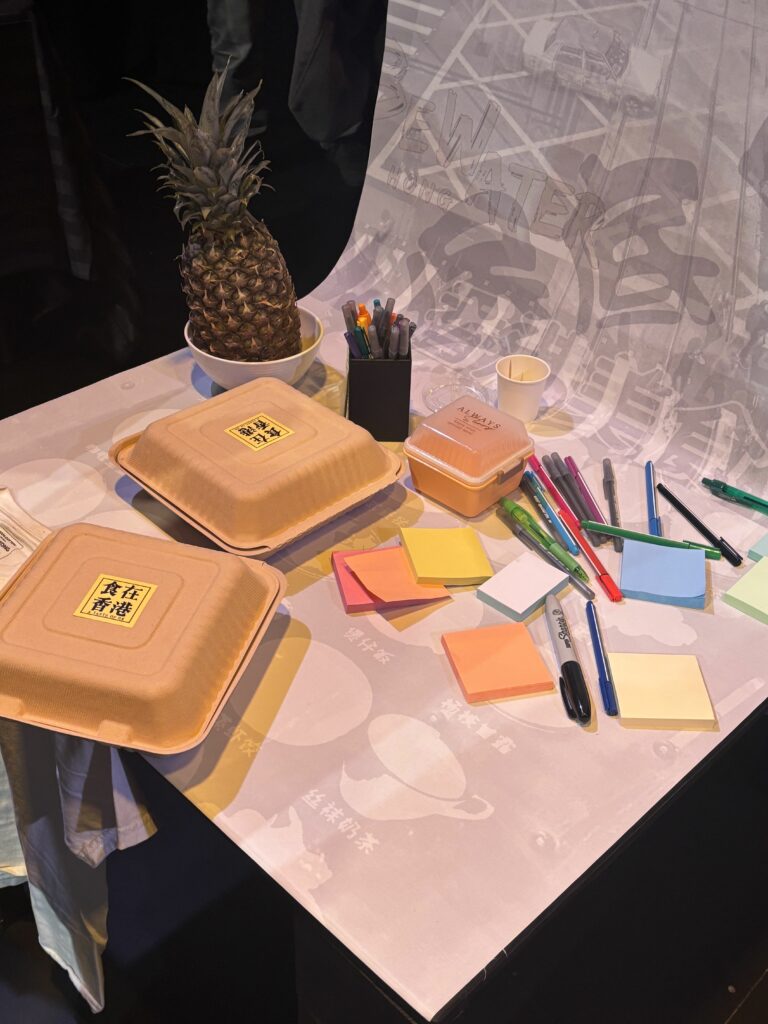

All this and more were present in A Taste of Hong Kong, a cultural tasting experience put on by Vancouver Asian Canadian Theatre and Pi Theatre detailing the rich and tasty culture of Hong Kong. Shown from March 6 to 15 at The Cultch, the performance starred SFU alum Derek Chan in the role of Jackie, an immigrant from Hong Kong.

When I first read the synopsis of this performance, I knew I needed to bring my dad. Despite having lived in Vancouver for the majority of his life, his penchant for Hong Kong delicacies like gaa lei jyu dan 咖喱魚蛋 (curry fish balls) never left. From the moment we stepped into the cozy theatre and saw the classic ceramic bowls and soup spoons synonymous with dim sum, it was clear that we were in for a treat. I just didn’t know how bittersweet said treat would be.

Jackie stepped onto the stage with the springy energy of a cartoon character. He welcomed the audience with a land acknowledgement that segued into a story of Hong Kong’s history. Dressed in the skater-like attire of tan cargo pants and a toque, his laid-back appearance contrasted the emotion that would soon hit the stage.

As Jackie walked us through some of Hong Kong’s oral history, I watched on as my dad chuckled at subtle references to Hong Kong culture. We were elated when he introduced us to the first dish of the night — bolo bao 菠蘿包 (pineapple buns), a family favourite. The performance went on with a jovial feel, with Hong Kong classics resurfacing as theatre volunteers handed out little paper cups with gaa lei jyu dan and siu mai 燒賣(pork and shrimp dumplings). The fish paste that Jackie substituted into the siu mai recipe reminded me of my grandma’s yu bing 魚餅 (fish cake), while the smells took me back to Sunday night dinners at her house.

Throughout the performance, Jackie occasionally broke out Cantonese phrases that my dad recognized — though I only understood bits and pieces. It was heartwarming hearing Jackie talk about jyut beng 月餅 moon cakes, another favourite of my dad’s, and watching his face light up from beside me as the performer told stories learned in Hong Kong classrooms throughout all time.

“The loud moments of the performance were loud, but the quiet moments were even louder.”

It was heartwarming until he suddenly cried “m hou daa ngo 唔好打我 (don’t hit me)!”

The performance shifted. Jackie’s story turned from the lighter-hearted retellings of food and snacks, to how these meals connect to the broader theme of the night: the spirit of the Hong Kong people. My dad and I both watched, completely engaged, as Jackie continually cried out “lok gan jyu 落緊雨 (it’s raining)!” — a term known by protestors in Hong Kong similarly to how “elbows up” is known in Canada. The spotlights grew harsh, and the shadows even harsher, as Jackie delivered a masterful retelling of his experiences in Hong Kong during the 2019 protests. The loud moments of the performance were loud, but the quiet moments were even louder.

You could hear a pin drop as Jackie took pauses in his storytelling, catching a deep breath with every outpour of emotion. Even with the occasional joke sprinkled in, the mood of the theatre was never the same after that. Throughout his recollection of riots filled with tear gas and unfurling umbrellas, there was one phrase sprinkled throughout his narrative — something uttered by the protestors and those who supported them — ga yau 加油. I was too enraptured with the performance to ask my dad for a translation.

As Jackie introduced the final dish, jook, the audience sat in a mournful silence. I had always come to associate jook with getting sick, since that was something my mom and grandma fed to us when we came down with a cold — but after having A Taste of Hong Kong, the dish has taken on a whole new meaning.

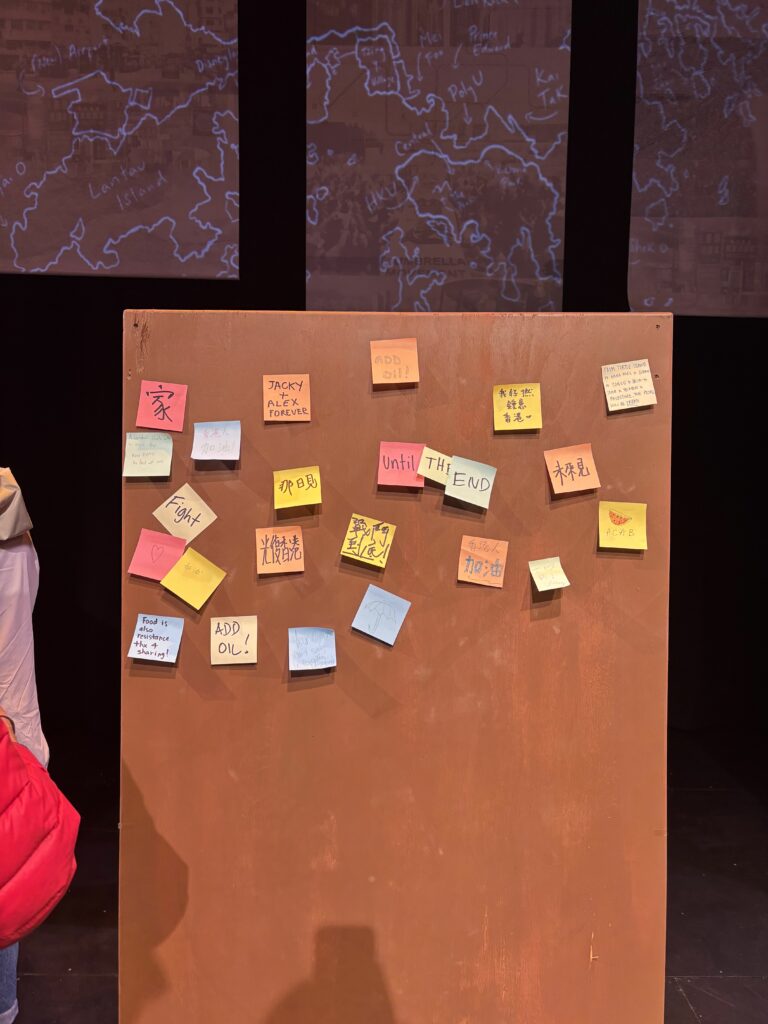

At the end of the performance, Jackie leaned one of the tables up so it resembled a wall. On it, he posted a single sticky note with characters written on it, encouraging us to do the same. It was a reminder that no one is ever alone, regardless of the circumstances they found themselves in — from protest camps, to Turtle Island, from the river to the sea. As my dad and I examined the growing collection of sticky notes, I pointed out one specific phrase that seemed to reappear.

“Add oil,” I asked my dad. “What does that mean?”

“Ga yau,” he said. “Keep going.”

Check out vAct.ca and PiTheatre.com for upcoming shows.