Written by: Michelle Gomez, Staff Writer

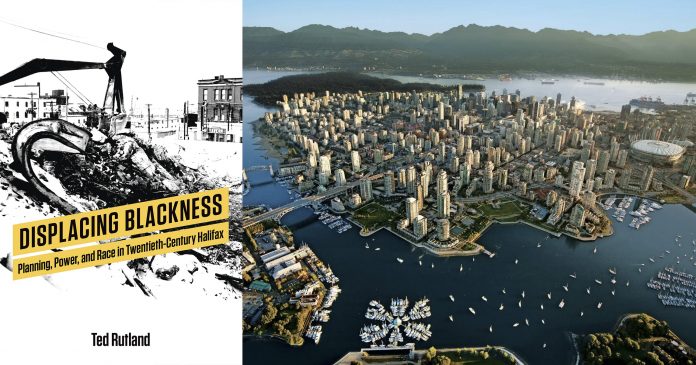

A public lecture held at SFU Harbour Centre on October 24 tackled the issue of how urban planning constantly fails to consider the Black population. The talk was held by Ted Rutland, associate professor in the department of geography, planning, and environment at Concordia University. Rutland structured the lecture around his book, Displacing Blackness: Planning, Power, and Race in Twentieth Century Halifax.

The book used Halifax, Nova Scotia as a case study to examine how the Black population has historically been displaced during urban planning by being pushed to the outskirts of major cities. It also critiqued current urban planning literature and offered suggestions to fill in the existing knowledge gaps.

Rutland began the lecture with an excerpt from his book, summarizing the history of urban planning in Halifax and how it has consistently neglected to consider Black residents.

“While we’re a long way from Halifax, we’re not outside of the orbit, of course, of anti-Blackness or Black displacement. Vancouver has its own history of anti-Blackness that dates back at least to the 1850s,” he explained.

Before discussing the book in detail, Rutland also acknowledged his own privilege as a white author writing about the presence of anti-Blackness in urban planning.

“My privilege to write this book as a white scholar depends on a series of racial privileges that are tied in various ways to anti-Blackness, and [ . . . ] the analysis in the book is derived from a long history of Black intellectual production,” he said.

“This book rests on the courageous work of others.”

Rutland then introduced his book’s three key themes. The first is about identifying racial oppression as a key phenomenon at the core of urban planning. Accordng to Rutland, much of the literature on city planning focuses on economic oppression rather than racism, referencing race “strictly in the language of poverty and access to resources” and placing urban planning as “this unique realm where racism doesn’t operate.” Rutland explains that this is problematic because racial oppression actually plays a very large part in city planning.

The second theme is about recognizing racism as something that exists in every part of urban life. Again, Rutland critiques the existing literature, as it “tends to focus on very specific spaces and lives, generally places where people of color are more likely to reside,” ignoring other spaces and assuming that racism does not operate in white spaces.

The third theme looked at how Black social movements are categorized and how this categorization can be problematic for planning. Currently, literature on Black social movements discusses them in various categories, including civil rights, Black power, and environmental. Rutland explained that, while this categorization is accurate (because that is how these movements classify themselves), “these movements are [also] concerned in one way or another with planning.” He emphasized that planners must not separate these movements from the discipline of planning and must look at the planning-related demands that these groups make.

Rutland concluded by summarizing his suggestions to improve the way planners approach their discipline, and explained how these suggestions would help fulfil the three key themes outlined above. Lastly, he stressed that while his analysis was focused on Halifax in the twentieth century, it can be applied to us in Vancouver in 2018.

Rutland ended the lecture with a quote from his book, stating that a different future requires us “to leave our place within the boundaries of humanity that has always depended for its coherence on the dehumanization of others [. . .] A new form of planning, one released from its centuries old connection to race and power will be created here, or nowhere.”