By: Katarina Chui, SFU Student

One: The introduction

I was born in Vancouver to two Hong Kong-born immigrants. I’ve had the privilege of growing up in two cultures: a culture found in my home, family, and church, and a culture in my school, friends, and overall community. I have a foot firmly planted in each world, because I have simultaneously experienced both these cultures my entire life. I recognise my privilege. I am neither a stranger in Canada nor in Hong Kong, because I’ve always known and loved both.

I’m one of the lucky ones, the ones who grew up living the outcome of the choices their parents made. Choices that were repeated by many across the world, spanning decades, ages, and socio-economic statuses. Hearing immigration stories from immigrants of different backgrounds and their journey to a new identity is a crucial aspect to understanding each other, and perhaps ourselves, better.

I asked my friends, their parents, family friends, and others in the Asian-Canadian community to share their immigration stories. These are deeply personal stories, and pseudonyms were given to some interviewees in order to protect their privacy. While everyone came to Canada for various reasons, there is one recurring theme: the search for something . . . different. Better. New.

Two: The journey

When discussing Asian immigration to North America, the difficulties of crossing the ocean are usually the first things mentioned. I hear harrowing stories of months spent on a cramped boat, fleeing a war-torn country in hopes that the West brings the solace they so desperately want. I hear the gamble people take, spending their last penny to come to North America with nothing but the clothes on their back, and perhaps a few treasured possessions, if they’re lucky. I hear stories of families separated, a parent going ahead to North America alone in order to lay the framework down for a reunion on Western soil. I hear stories of those who make it, and others who don’t. The journey to the West is a mentally, physically, and emotionally taxing journey, one where the hope for a better future is their anchor and motivator to start a new life in a foreign city.

Hope — it’s uncertain, but the belief of a better future is stronger than uncertainty, or second-guessing. They want a better future, be it for themselves, their children, or future generations.

The thing is, the hardships don’t end there.

The future they aspire to have is a future they will have to build from scratch.

Three: Adaptation and choices

Adaptation and assimilation into a new culture is hard; in fact, adults and older teenagers often have a harder time accepting their identity as Canadians. In a 2011 press release by UBC psychologist Steven Heine, he noted that children 15 and under identify more with Canadian culture “with each passing year,” but those who immigrated to Canada after the age of 25 were found to have accepted their Canadian identity less and less.

Yet, despite the chance of being unable to adapt or assimilate to Canadian culture, forever destined to live amongst Canadians but separate from them, they still came. And stayed.

Four: Meaning of the dream

Word: A·mer·i·can Dream (/əˈmerəkən drēm/): noun. The belief that all American citizens should possess “an equal opportunity to achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and initiative.” This is attained by “sacrifice, risk-taking, and hard work, rather than by chance.”

What makes the Canadian Dream different?

~

My mother immigrated to Vancouver with her family in April 1994. My father immigrated here alone later that year. I sometimes wonder what type of courage it takes to get on a vehicle whose destination is in a foreign land filled with promise, while leaving behind everything you’ve ever known?

How can the hope for a better future, in a land thousands of kilometres away from your home and/or family, be so strong that you are willing to give all that up? How can they be willing to go through the struggles of learning a new language, adapting to a whole different culture, experiencing homesickness, and finding a community or even just a few people who speak the same language? The idea is almost too much too fathom, but they did it. Over and over. Be it for themselves, for their family, or for their children, both present and future, they did it.

The end goal of the Dream is not encased in gold and shining lights or the attainment of economic success, but rather, a single seed of hope, planted in each of their futures. I don’t think the children of immigrants will ever understand the significance of their parents’ actions.

I know I didn’t. I still don’t think I do.

Five: The other voices

Carol Lam, Jackie Tan, Nely Delisa, and Mr. Chou all immigrated to Vancouver in hopes of providing a better life, environment, and future for their children to grow up in. Carol left Hong Kong in 1995, when Hong Kong was about to rejoin China after 99 years under British rule. She was unsure of what the future brought with this change, and chose to immigrate overseas to either Singapore or Canada — the only two countries that accepted their immigration application. She decided against immigrating to Singapore as she didn’t want her sons partaking in the two-year mandatory military service. Both Jackie and Nely chose Canada due to the opportunities it brought, believing it would provide a better future for their families. Jackie knew Canada was accepting of immigrants, and believed she and her family would be welcomed there. While Nely’s husband got a new job overseas, she also believed the Canadian education system to be better for her daughter and future children. Mr. Chou echoed this sentiment, thinking Canada to be the safest country for his children, noting that he wouldn’t have to “worry about [ . . . ] someone [losing] his mind [and shooting] students [during] school.”

21-year-old Matthew Lewi came to Vancouver in 2017, drawn by the chance to start a new life overseas. He came to Simon Fraser University and began his major in communication, and since then, he’s worked hard on his English pronunciation, trying to blend with the locals. He’s succeeded on that front; there is no trace of an Indonesian accent in his spoken English. Some immigrants are not able to overcome the language barrier. Ita Ho finds the language barrier one of the hardest things for her to adapt to. Despite having lived in Toronto for almost 30 years, she still speaks broken English. Carol Lam, also a fellow Hong Kong native, has the same experience. While the Hong Kong education system made learning English compulsory, she found that her spoken English skills were not sufficient. “I need to think so hard to communicate with the [locals],” she adds. “I [make] plenty of mistakes and [feel] so embarrassed when they [misunderstand] me.”

It is widely agreed that the “Canadian Dream,” as I like to call it, is built from the American Dream, but with the addition of peace, freedom, an appreciation for cultural diversity, and a dedication to inclusivity and equality regardless of background. Carol suggests that the Canadian Dream was probably built as such because “most Canadians are immigrants.” Most Canadians understand the courage it took to come to a new country, feeling thankful that they and their culture are accepted. The warm welcome they experienced may cause them to extend the same gratitude to others, with these values taught in educational settings and strengthened in cultural settings. Jackie strongly believes that the American Dream is not reachable these days, especially for immigrants, because they do not fit in with the mold of the “perfect” American, be it in language, appearance, or background. Racism is perceived to be less prevalent in Canada, a factor that was included in many people’s decisions to immigrate to Canada.

For some, the Canadian Dream is not an indicator of quality of life. Simon Chan and Mr. K came to Canada as young teenagers, not by choice but out of fear for their own safety. They fled to Canada with their families at the end of the Chinese cultural revolution in 1976 and when the Vietnamese political issues started taking ground, respectively. Their Canadian Dream was to simply escape and find refuge overseas. Ita thinks that a balance between working hard in her career and being able to relax after work is the “key to [a] high quality of life.” Mr. Chou agrees: a peaceful life is what’s important. In Canada, Mr. K adds, an uncertainty about tomorrow does not exist. “You don’t have to worry about whether you’ll have food, shelter, [or] family security [ . . . ] to wake up alive tomorrow.” Certainty. He fled from Vietnam due to uncertainty, and he’s found it here, in his second home.

Achieving the Canadian Dream does not equate to identity, however. Peng Leong, who immigrated to Vancouver from Malaysia as a newly graduated university student, says that, even years later, she does not consider herself to be Canadian, declaring her Canadian passport to be the only Canadian thing about her. An immigrant status may also hinder the journey to achieving the Canadian Dream. Simon points out that language barriers prevent individuals from easily expressing themselves, and people may “harbour resentment against ethnic minorities for ‘taking away their jobs’.” He’s seen first-hand the damage the language barrier can bring; his parents were not able to find jobs that reflected their level of education, and he himself laments the language barrier, calling that the one thing that prevents him from achieving more.

Despite having lived in Canada for over two-thirds of his life, Simon still feels like a foreigner sometimes. If someone who has spent the majority of his life in Canada still sees himself as “apart” from Canadians, imagine the separation those who came here later in life or immigrated in recent years can feel when it comes to their identity.

When asked, “What makes you most proud of being Canadian?”, many of the answers are less about identifying as Canadian or self-identity and more about the beauty of the Canadian landscape, the security and quality of life being on Canadian soil brings, and the overall acceptance of immigrants and refugees.

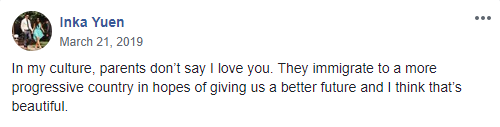

Many of these individuals sacrificed everything in order to live in a country they do not consider their own, to live in a country they feel no connection to. They allowed themselves a potential lifetime of feelings of isolation, a lifetime of living thousands of miles away from their family, and a lifetime of difficulty communicating in a language not their own . . . just so their children can have a better future.

Six: Our legacy

I, like many other first-generation Canadians, have had the privilege and honour of growing up in two cultures: my family’s and Canada’s. I, like many of my interviewee’s children, grew up speaking, living in, and experiencing their ethnic culture at home, and adopting their native or near native Canadian identity when outside, be it at school, with their friends, or in public.

Matthew describes Canada as an extremely open-minded country about different cultures as opposed to a country with a singular set of traditions and beliefs. Multiculturality is frequently mentioned, both in Toronto- and Vancouver-based interviewees, with many mentioning said existence in Canada to be an asset in retaining their own cultures. For Jackie, multiculturalism allows her to celebrate both identities without forfeiting either one, and Simon says that the addition of modern technology gives us easy access to retaining and learning about our ethnic cultures, languages, traditions, and histories. Traditional recipes are just beyond our fingertips — as Nely points out, it is another way to remember your roots and the values that come with your culture.

I dare say that children of immigrants have an obligation to remember their culture. We cannot deny that is a large part of us and our history. We are privileged enough to grow up in a country that encourages multiculturalism; the least we can do is preserve it and introduce it to future generations. Our families did not come here just for us to lose a piece of ourselves. Our background is part of our identity; our upbringing is shaped by the culture. Our parents left family and loved ones behind as they sought a new life overseas; we should not forget them.

Identity is more than the place we grew up in, more than the place we love, more than the place our ancestors came from. It’s found in the foods we grew up eating, the familiar call of “sik faan lah!” (“dinner’s ready!”), the values and morals instilled in you, the stories and traditions we might not understand but still hold dearly, and a feeling of comfort and home whenever you think of it.

Mr. Chou can already witness the fruits of his decision. Giving his children an opportunity to learn English properly, succeed, and be happy . . . that’s all he wanted.

And they are.

We all are.

End: Reflections

[…] Continue reading on the source site here. […]

[…] Source link […]