I’ve been a Woody Allen fan for as long as I can remember. My first Allen picture was Annie Hall, which I watched before I was old enough to understand any of its dense cultural references. From there, it was Manhattan, Broadway Danny Rose, Hannah and Her Sisters, Interiors, and Bullets Over Broadway. The music, the performances, the wry self-awareness of the characters — all of these aspects, common themes in Allen’s filmmaking, appealed to my preteen sensibilities.

I was hooked. I’ve spent the latter decade of my life loving Woody Allen’s films, and in their own way, they’ve influenced my view of the world around me. There’s an everyman quality to Allen’s neurotic avatar that seems to speak volumes about my own life, and to this day I consider these films to be among my very favourites.

Unlike many of those who have written similar pieces to this one in recent weeks, I had very little knowledge of Allen’s sexual abuse allegations until Dylan Farrow, his adopted daughter, penned an open letter earlier this month detailing her experience, which was published in part in The New York Times. “When I was seven years old, Woody Allen took me by the hand and led me into a dim, closet-like attic on the second floor of our house,” she writes. “He told me to lay on my stomach and play with my brother’s electric train set. Then he sexually assaulted me.”

For those of you who haven’t, I encourage you to read Farrow’s letter, which is posted in full on Times writer Nicholas Kristof’s blog. Though one might question whether it is fair that Kristof — a personal friend of the Farrow family — used his position at the paper to give Farrow’s message a platform, it’s hard to know whether such a thing would have gained attention anyway. Farrow’s account is harrowing and detailed, calling to task Hollywood, and particularly artists who have worked with Allen, for silencing her and other abuse survivors.

“What if it had been your child, Cate Blanchett? Louis CK? Alec Baldwin?” She asks. “You knew me as a girl, Diane Keaton. Have you forgotten me?”

I do not know what happened between Woody Allen and Dylan Farrow — nor do any of the journalists, lawyers or family members making statements, one way or the other. There are only two people who know for sure, and a wide range of opinions and speculations in between.

Allen apologists will cite the Yale–New Haven Child Sexual Abuse Clinic, who testified in March 1993 that no abuse had taken place. Those on the other side will counter by saying that a state attorney at the time stated there was “probable cause” to convict Allen, but the case was dropped in order to spare Dylan unnecessary trauma. In a custody case between Farrow and Allen, Judge Elliott Wilk called Allen’s relationship with Dylan “grossly inappropriate.” Mia would go on to win custody over Dylan, as well as seven more of her nine children.

But without much in the way of concrete evidence, how should we choose to judge the Woody Allen case? Your first instinct might be to say that it’s wrong to side with either party, and that it’s none of our business, anyways. But there is no middle ground here. You’re either with Allen, or you’re against him.

~

Days before Dylan’s letter was published, Woody Allen was awarded the Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievement in filmmaking from the Hollywood Foreign Press. At the Golden Globes Award ceremony, Diane Keaton fumbled through a sentimental speech in praise of Allen’s artistry and his female characters who, in her words, “can’t be compartmentalized.” Winning the Best Actress in a Drama statuette for her role in Allen’s latest film, Blue Jasmine, Cate Blanchett echoed Keaton’s praise, saying “we take him for granted.” Applause filled the room.

Allen’s lawyers have argued that Farrow’s account, which they believe was “implanted in her” by mother Mia Farrow, was timed to coincide with the awards season, in order to undermine Allen’s chance of winning accolades for Blue Jasmine. Others, such as documentarian Robert B. Weide in a now-infamous article for The Daily Beast, have suggested that the scandal was a strategy to promote Ronan Farrow’s upcoming show on MSNBC, as well as a chance for Mia to publicly lash out at her former partner. Moses Farrow, Dylan’s brother, has publicly defended Allen, saying that Mia forced Dylan into believing that Woody had assaulted her.

But though Weide and others — including Allen himself, in a written response published just days ago in The New York Times — are quick to question the motives of Mia, Ronan, and other public detractors of Allen, their arguments are borderline ad hominem: whatever any second or third party’s feelings or motivations towards Woody, this isn’t about them. It’s about Dylan Farrow — whose name change is offhandedly revealed by Weide, despite her clear intention to keep it hidden — and her testimony.

I don’t know what happened, but I know that I stand with Dylan Farrow.

This may seem counterintuitive to many of you, but we must remind ourselves that we aren’t lawyers, judges, or jurors — the court of public opinion is not a court of law, and if my belief that Allen is guilty turns out to be untrue, no one will have spent undue time in jail, and I will apologize for my error. But if I believe the opposite, and I am proven wrong, I will have been complicit in letting a survivor’s story fall on deaf ears, as these accounts too often do in our society.

For every Dylan Farrow, there are thousands of men, women, and children whose stories will never be told. For me, the well-meaning Woody Allen fan who only recently learned of the allegations against him, Farrow’s story might never have reached me. Given that it has, I am inclined to believe it.

A recent article by Michelle Dean for Flavorwire touches on the uncomfortable truth of issues such as these: that there is no such thing as an impartial stance. “If you find Farrow’s letter easy to dismiss, because you like Allen’s movies,” she argues, “you’re just as guilty of this so-called ‘rush to judgement’ as anyone else.” Aaron Bady’s piece in The New Inquiry raises a similar point: “The damnably difficult thing about all this, of course, is that you can’t presume that both are innocent at the same time. One of them must be saying something that is not true.”

For every Dylan Farrow, there are thousands of men, women, and children whose stories will never be told.

Some will choose to ignore the debate entirely, not to get involved and to wait for the issue to sort itself out. But, like the Hollywood Foreign Press, who have supported Allen’s art without so much of a mention of Farrow’s allegations, you are implicitly devaluing her story. Not to pay attention is to allow Allen, and indeed all others like him, to get away with it. To do nothing is to support him.

~

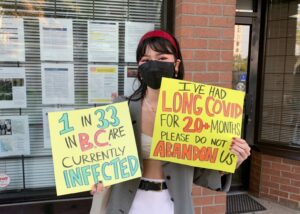

All of us live in a rape culture. Many of you will have heard this term, but not all of you will know what it means — a rape culture is one where we question Farrow’s account before we question Allen’s guilt, one where unfounded accusations of rape are cited over unreported assaults, one where we are taught to avoid attracting sexual violence but rarely reminded not to perpetuate it. A culture where, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, an estimated 60 per cent of rapes go unreported, and only three per cent of rapists ever see the inside of a jail cell.

Our culture is one that devalues the experience of victims and protects those who are accused of sexual violence. Though it would be inaccurate to presume that statistics have a direct bearing on Woody Allen’s case, they are illuminating nonetheless: on a worldwide scale, the National Centre for the Prosecution of Violence Against Women estimates that between two to eight per cent of rape charges are later determined to be unfounded.

This number is often assumed to be much higher, as our cultural conversation tends to hinge on the veracity of a victim’s story and their corresponding mental state. Look at Wiebe, whose article cites descriptions of Farrow as “mentally unstable.” Look at Stephen King, whose quickly deleted tweet concerning Farrow’s “palpable bitchery” focuses the debate squarely on her person rather than her experience.

In these instances, Farrow is not a human being but an archetype on which our assumptions about women and the sexually abused are projected.

Arguments claiming Dylan’s status as a pawn between quarreling exes Mia and Woody further depersonalize her: entrenched in the culture of celebrity, she is faceless, and has no iconic presence to be measured against. She is a statistic; Allen is an icon.

Too many of these debates have centred around Allen as a filmmaker and a cultural presence while framing Dylan as an outsider, a troubled child turned troubled adult who was either brainwashed by her mother or otherwise fundamentally disturbed. But it’s important to set a precedent of believing those who speak out against sexual assault: there is less to lose in the occasional unfounded accusation than there is in fostering a culture where survivors are encouraged to stay silent, and made afraid to share their stories.

In arguing for her case — which, even if untrue, she inarguably believes to have happened — Dylan has shown remarkable bravery and heroism. In supporting it, we can advocate for a more tolerant society which accepts and embraces those who survive sexual abuse.

Hollywood has a talent for marginalising the voices it doesn’t want to hear. It’s the reason that African-Americans so rarely win awards, and stories of slavery and colonialism are so rarely told. It’s the reason that challenging films like The Master and Amour lose out to crowd pleasers like Argo. It’s the reason popular films fail the Bechdel test year after year, and it’s the reason artists that beat their wives and spew racial slurs are quickly and overwhelmingly forgiven.

But we as viewers have the opportunity to reject the homogenized “reality” that Hollywood presents to us. We can choose to give voice to the voiceless, even if it means risking being wrong about a public figure whom, two weeks ago, I would have counted among my favourite artists without second thought.

Still, the question remains: can I still include Allen on that list? If we are to believe Dylan Farrow, and accept the belief that Woody Allen is a sexual predator who molested his seven-year old adopted daughter, how should we look at his films? His plays? His music? Is it possible to separate, as is so often debated, the art from the artist?

~

The great Jewish conductor Daniel Barenboim once said of Richard Wagner, “he never composed an anti-Semitic note.” Wagner, one of the staunchest anti-Semites of his time, is generally looked down upon in Israel and other Jewish communities. If we are speaking of overtly anti-Semitic artists, we must also mention T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Edgar Degas, all of whom wrote extensively on their negative views of Judaism.

The list, of course, does not stop there. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, arguably the cinema’s first masterpiece, was so strongly in favour of the Klu Klux Klan that the organization went on to use the film as a recruitment tool for decades afterward. Twenty years later, Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will depicted the 1934 Nuremberg Rally in Nazi Germany with striking beauty and brilliant filmmaking technique — you’d be hard pressed to find a modern documentary or advertisement whose approach can’t be traced back to the Riefenstahl.

Hollywood has a talent for marginalising the voices it doesn’t want to hear.

Lord Byron engaged in incest. Gustave Flaubert paid for sex with underage boys. Norman Mailer tried to kill his wife in a drunken rage. John Lennon and Pablo Picasso, among many others, were said to physically abuse their family members. I could go on, but my point has been made: if you eliminate artists whose views and personal lives you disagree with, you end up crossing a lot of names off of your list.

As Jay Panini wrote in “Room for Debate”, The New York Times news blog, “Being an artist has absolutely nothing to do with one’s personal behavior. Wonderful human beings can be dreadful poets, painters, filmmakers, musicians. The reverse is equally true: hideous people can make great art.”

This is a fundamental truth. Even if Woody Allen the person and Woody Allen the artist prove to be incongruous, Manhattan is still the same film I’ve seen a dozen times. As much as I’d like to retroactively detach myself from my emotional and intellectual reactions to Allen’s art, I don’t know if I can. If Allen is a bad person, he is a bad person who makes good art, even if that art is fundamentally altered by revelations about his character.

So what are we to do with Allen’s filmography? We can boycott his movies, in order to deny him the royalties and fame that come with his ongoing success — but is this fair to the artists who have worked with him, such as the immensely talented film editor Susan E. Morse, who worked with him from 1977 to 1989? What about all of the actors involved in his works, from Diane Keaton to Cate Blanchett, from Dianne Wiest to Scarlett Johansson? They may be implicit in silencing survivors, as Farrow argues, but is this enough reason to boycott their work as well?

Perhaps the most often cited analogue to Woody Allen’s case is that of Roman Polanski, who pleaded guilty to the sexual assault of a 13-year-old girl in 1977. His films are among the most celebrated in Hollywood: Rosemary’s Baby, Chinatown, and The Pianist — which won him Best Director in 2002 — have all been lauded as masterpieces. As in Allen’s case, the Hollywood elite has gone to great lengths to minimise the effect of Polanski’s crime. Whoopi Goldberg even went so far as to refer to the assault as “not rape-rape,” and many have expressed similar defenses.

Unlike Allen, I have been aware of Polanski’s crimes since before I ever watched one of his movies. I have not boycotted them, and have not decried Polanski’s status as a famous filmmaker as a result of his actions. However, each viewing is tempered by my knowledge that Polanski has committed horrifying acts, and that his status as a gifted and sometimes brilliant filmmaker does nothing to diminish this fact — how could it?

~

I applaud those of you who will decide, unselfishly, that you would rather deprive yourself of Allen’s artistic work than support a man who may have raped a seven-year old girl. However, I can’t count myself among you. It’s likely that I will rewatch many of Allen’s films in the next year with a new perspective, and I have no idea whether or not this will affect their value. It’s hard for me to reconcile the 10-year old kid who fell in love with Annie Hall and the 20-year old undergrad who just wrote an article condemning its director — maybe I’ll never be able to.

But this is our relationship with art: as we evolve and our viewpoints change, so too does our reaction to and opinion of the cultural products that we hold most dear. Maybe Allen will still make my list of best-ever filmmakers in a month; maybe not. All I can say for sure is that I’ll never see Annie Hall the same way again.

Update: Read Dylan Farrow’s response to Woody Allen’s op-ed here.