By: Anonymous SFU Student

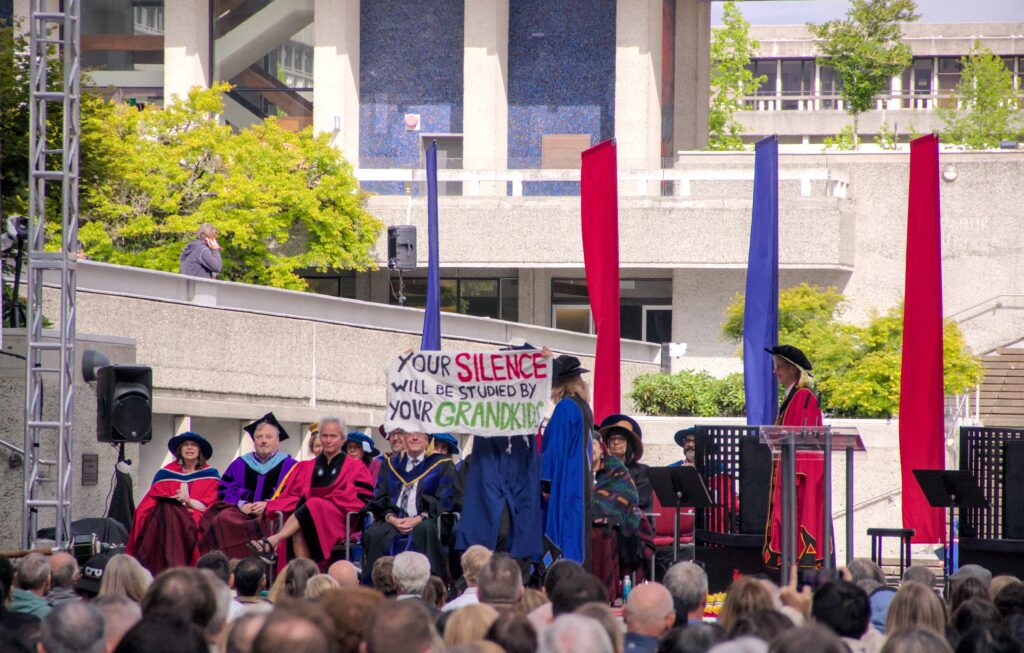

As of writing, 58 days have passed since the encampment at UBC began. Despite our united front, we still struggle to achieve our goals: demanding that UBC divests, academically sever ties with Israeli universities, and condemn the genocide in occupied Palestinian territories. Similar demands from SFU students have occurred recently. While SFU doesn’t have an encampment yet, students and faculty have intervened at convocations and occupied the downtown library to demand divestment. Both UBC and SFU need to understand the urgency of divesting from companies complicit in the Palestinian genocide, and listen to the voices of their students and community. I come into this space as a student, empathetic toward Palestinian people’s fight for their freedom, shaped by my South East Asian heritage and the legacy of colonization. Many of my comrades are united by similar experiences of oppression.

This isn’t the first time an effort for UBC to divest from problematic institutions has happened. Back in the early 2010s, the fossil fuel divestment protest was just starting. These protests lasted several years and were led by student groups like Climate Justice UBC (then called UBCC350) and faculty members, continuously pushing UBC to divest from fossil fuel companies. It wasn’t until 2019 when UBC finally committed to divest — it took them nearly a decade. Similarly, at SFU, it took years of work from student groups like SFU 350 for SFU to finally declare a climate emergency and later divest from fossil fuels. Unfortunately, the history of UBC’s slow action to enact student demands means the current encampment will likely take longer than the almost two months it has stood. However, continuous support for Palestine gives hope for the encampment to keep moving forward.

This made me think for quite some time, especially about why people continue to show up and hold down the camp after so many hardships.

The UBC encampment for Palestine has been going strong since April 29. Working as a horizontal organizational structure, the encampment is a leaderless, non-hierarchical space where everyone is equal. We have groups in charge of different tents related to the daily operation of the camp, including food, safety, supply, medicine, art, and library. General meetings are held as frequently as possible and are the only platform to decide the goals of the encampment. It is a process of direct democracy where everyone’s voice is heard and considered, with final decisions being made based on majority votes.

Everyone who shows up to this camp is intelligent, kind, and capable of doing great things, however, we are humans, and deep down, we all seek a sense of belonging. This whole encampment is like a community, and within it, each tent is part of the group. However, it did not always feel like a cohesive community. Before the camp reached this structure, it was run by multiple “invisible” hierarchies.

This encampment makes me hopeful about a future where people can afford to contribute in their own meaningful ways.

Initially, there were instances where outgoing white, cisgender, and conventionally-attractive men were automatically assumed to be smart, reliable, and worthy to make decisions, while non-conforming and marginalized individuals had to work harder to be acknowledged. I don’t think this was done purposely, but can be attributed to the mixture of pressure at the encampment and the unconscious biases ingrained in colonial ideologies. The constant struggle to have all our voices heard caused tension in the supposedly democratic structure, as well as relationship mistrust in the camp. This was not what I and a lot of comrades expected from this space, where solidarity with Palestinians against colonization demands democratic practice and decentralized decision-making.

As a young, gender-non-conforming person of color, my voice was often overshadowed in favour of white, cisgender campers. We took time to acknowledge and address these biases and hierarchical structures and we came up with alternative ways to ensure every voice was heard. I believe our camp is being managed in a more inclusive way, moving toward good causes, rather than replicating oppressive systems.

I acknowledge it’s hard to be trusting and welcoming when comrades don’t even know each other’s real names — we use camp names to protect our private identity. More so, we are under constant surveillance from UBC and the RCMP, but trust and hope are the elements that keep this encampment together.

It doesn’t mean we stop practicing security culture. It’s vital to be self-aware and follow safety protocols, such as not engaging with cops and agitators, and having a dedicated media liaison. However, there is a saying at the camp: “We keep us safe.” My way to build trust has been working at different tents, getting to know different comrades, and observing their behaviors. Over time, trust and relationships are formed.

When I forgot to go to work one afternoon while I was at the encampment, I was so worried at first, but then relief came, because the encampment is a solidarity movement and addresses the basic needs our institutions are supposed to handle. This includes food, shelter, supplies, and medicines, all coming from community donations.

We welcome visitors who are food insecure and/or unhoused. In exchange, campers offer their labor, time, commitment, and protection to the community. We have space for nurturing relationships, reading, doing art, hosting teach-in sessions on Palestinian resistance and cinema, playing music, and do not contribute to the capitalistic systems actively funding genocide and oppressing Palestinian people.

I believe our camp is being managed in a more inclusive way, moving toward good causes, rather than replicating oppressive systems.

Ever since I joined the encampment, I’ve asked every new comrade I’ve met on shifts whether they’re a Zoë or a Zelda. The Zoë and Zelda theory, invented by the creator of my favourite show BoJack Horseman, is about two twin sisters with completely different personalities. Zoë is the serious, cautious, and sometimes cynical person who prefers quiet activities like reading and tends to avoid big crowds. On the other hand, Zelda embodies outgoing, optimistic, and energetic individuals who enjoy social activities and are full of life.

Everyone gave interesting answers to this question. Some are optimistic, lifting the spirits of fellow protestors and smoothing out the high-stake environment we are all in, the Zeldas that reignite our hope. Others are more like Zoës: cautious, patient, and have keen critical thinking and conflict resolution skills. However, no matter how serious or cynical some people are, everyone in this encampment brings hope that we are fighting against oppressive systems, that we are fighting the good fight.

This encampment makes me hopeful about a future where people can afford to contribute in their own meaningful ways. There are those who are making sacrifices to stand for their beliefs, for what they consider righteous. Others come and contribute to the encampment just by showing up in solidarity with the protestors. I acknowledge that for me, being able to volunteer at the encampment is a privilege. Policing people for not being able to join the encampment is not fair, considering we come from different walks of life.

We are trying our best here, and I’m proud of all my beautiful comrades for what we’ve been fighting for. Our demands for UBC are clear: disclose, divest, and cut ties with Israeli universities that are complicit, as well as condemn this genocide. We demand UBC stop the RCMP’s intimidation and surveillance of their students. This should not end here, I hope in the future we can demand UBC fully fund tuition for Palestinian students.