By Amirul Anirban, Peak Associate; Jacob Mattie, Opinions Editor

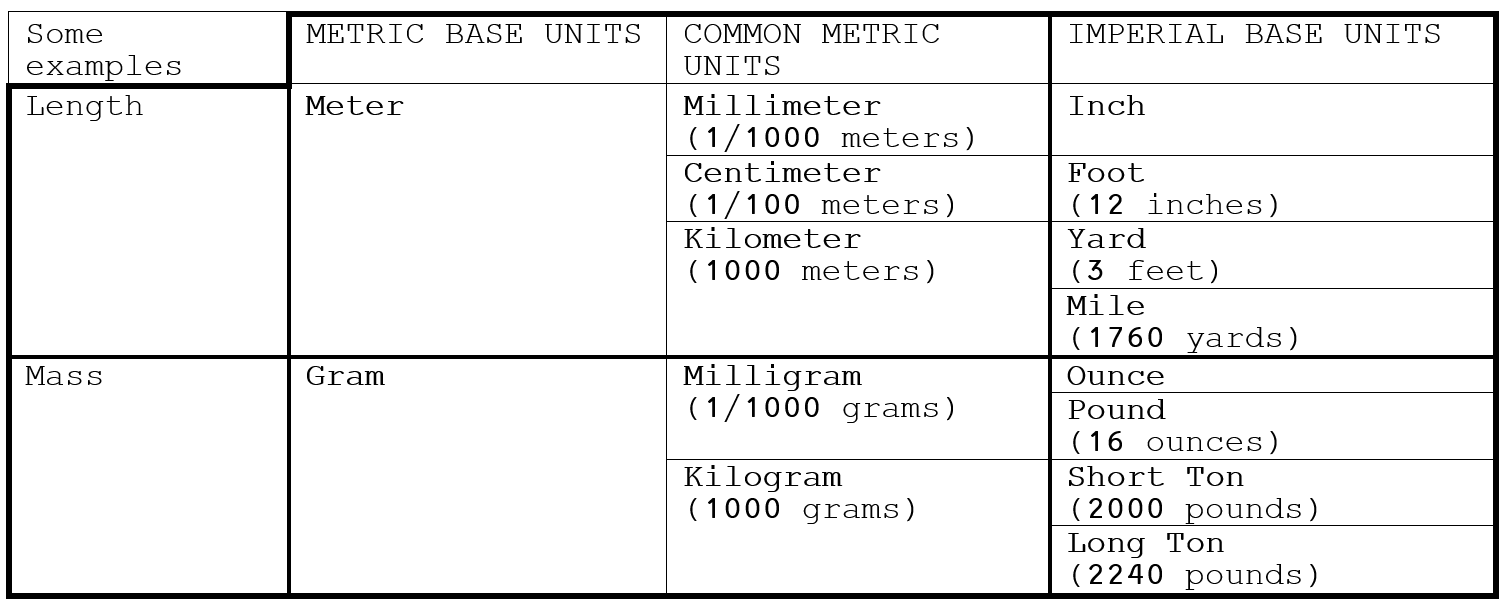

One pound is sixteen ounces, and one ounce is sixteen drams. Two thousand pounds makes a short ton, but 2,240 pounds makes . . . a long ton? The above convoluted measures are the mass units of the imperial system, and to convert between them is tedious at best. There’s plenty of room for blunders, and it’s well past time we scrap the system entirely.

The metric system, in contrast, is much easier — all commensurable units are separated by a factor of 10, and have standardized prefixes. Grams to kilograms? Easy — divide by 1,000. Liters to milliliters? Also easy — multiply by 1,000! Inches to miles, on the other hand? Uh. Give me a moment. Not only does the imperial system require you to juggle equations, but you also need to keep track of the irregular unit conversions. We’re not even addressing the imperial system’s abhorrent approach to volumes — while metric uses tidy units like cubic lengths (cubic centimeter), imperial volumes come in arbitrary sizes like fluid ounces (not to be confused with regular ounces) and gallons.

In an interview with CBC regarding trade with the US, University of Toronto economist Harry Krashinsky described the continued presence of the imperial system as an annoyance. Most nations have had the good sense to adopt the metric system, but here in Canada we use a mix — pounds, inches, and gallons are used alongside their metric counterparts of kilograms, meters, and liters. We’ll check the weather in Celsius (metric), but measure our oven temperatures in Fahrenheit (imperial).

It took until 1974 for government-sanctioned conversions to begin in Canada. The metric system was made compulsory by the federal government under former Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who said “the metric system is worldwide” and called the people who refuse to convert “dinosaurs.” Incidentally, Canada is home to the world’s richest dinosaur fossil beds, and we continue to hold a stubborn grasp on the imperial system.

In principle, every sector of Canada was converted to the metric system, but this isn’t quite the case in practice: our construction industry — which comprises roughly 7% of the workforce — relies on the materials we produce for the larger US market, and continues to work in imperial units.

We are left in an odd situation — in terms of global trade, the US, Liberia, and Myanmar are the only remaining countries that use the imperial system. Having to constantly route much of our trade through unit conversions creates at best puzzling situations. Foreign sales are given yet another layer of complexity, and unit conversion (or their lack) can cause disasters — take, for example, NASA’s $125 million dollar crash. A Mars orbiter’s navigation was set in metric, but its propulsion was measured in imperial units. The The ensuing discrepancy caused the spacecraft to skim too close to the planet and disintegrate in Mars’ atmosphere.

By now, it’s likely that the US is going to stick with imperial. But as international trade grows, we can do more than build ourselves around our southern neighbours. The rest of the world is in metric — let’s see how we measure up.