by Meera Eragoda, Editor-in-Chief

What does it mean to be a racialized immigrant in so-called BC? It usually means your history in this place isn’t told very often. The beginnings of BC have historically been painted as rough-and-tumble white explorers carving their way through the wilderness, bringing with them “civilization.” We now know, of course, this land has a rich, Indigenous history which predates settler colonialism by tens of thousands of years. Through a four part documentary series British Columbia: An Untold History, the Knowledge Network brings some of these stories to light.

The show premiered October 12 and two episodes have already been released: Change + Resistance focuses on the Indigenous resistance to settler colonialism and Labour + Persistence covers the labour movement in BC. Upcoming episodes are Migration + Resilience and Nature + Co-Existence. The former covers the immigrant history of BC and the latter, the environmental history, including Indigenous stewardship of this land.

Migration + Resilience is set to air October 26 and it is worth the watch if you’re looking for an overview of the history of Chinese, Japanese, Punjabi, Black, and Doukhobor communities in BC. My experience with the way immigrant histories in BC have been traditionally told is they barely scratch the surface of Chinese and Japanese history, and usually omit any South Asian histories or the histories of other racialized communities.

South Asian Roots

Watching the episode, I was struck by one of the speakers, SFU alum and cultural researcher and curator, Naveen Girn. His care with Sikh history was evident and — despite how packed the episode was — was able to drop tantalizing hints as to the complexity of tackling this history. I was fortunate enough to speak with him to delve deeper into the history of South Asians in BC. We both related to the experience of not having any South Asian history covered in high school. Being a first generation immigrant, for a long time I just assumed there wasn’t any. I’m Sri Lankan and our history here started later. However, as Girn, who has been dedicated to daylighting the history of the South Asian community “for over a decade” explained, the Sikh community has deep roots in BC.

Many of the “early trading ships [ . . . ] had Hawaiian and Filipino and Chinese sailors working on board and there are some stories of South Asians from the Bengali area being on that as well,” he said. The first documented immigration of South Asians began in the 1890s and early 1900s. Girn spoke about a “Sikh regiment that was invited to the Jubilee of Queen Victoria.” He said they were “celebrated for being part of the Empire” and when they went home, they took with them stories of Canada’s beauty and opportunity, spurring an influx of Punjabi and Sikh immigration, along with a few Fijians and others. In fact, the first Sikh gurdwara (temple) opened in Golden, BC, likely in around 1905–06, and was converted from a barn.

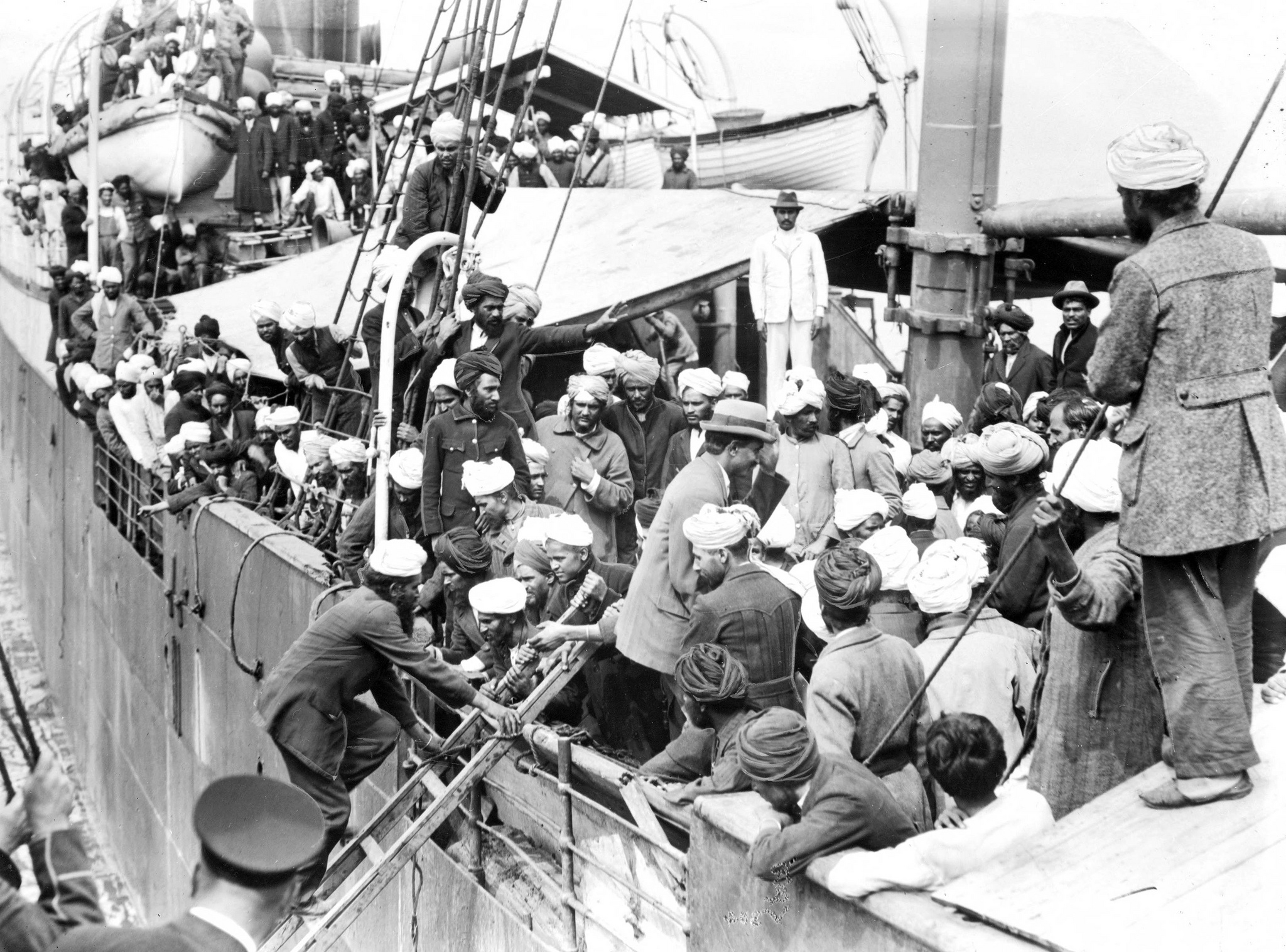

Girn details the history of the Komagata Maru in the documentary. This was a ship commissioned by Gurdit Singh Sirhali, a Sikh from Punjab. Sirhali was responding to Canada’s amendment to the Immigration Act which refused passage to anyone who couldn’t make the journey in one continuous trip — a roundabout way of banning racialized immigrants, such as those from India. In April 1914, over 350 Indians (Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus) made the journey from Hong Kong, but when they arrived, were not allowed to dock and were sent back on July 23, 1914. The episode goes into this event in greater detail, highlighting its importance.

In the episode, Girn points out the established South Asian community was able to raise $60,000 for the legal defense of the occupants of the ship, noting how difficult this was “when people are being paid less than a dollar a day.”

Cross-community collaboration

There is one picture Girn lingers on in the episode’s recounting of the 1907 anti-Asian riots — when white settlers made their way through Chinatown to Powell Street, smashing windows and assaulting residents. It’s a black and white image taken of a shop on Powell Street after the riot and in the corner are two Sikh men. The image compels him for what it represents: cross-community collaboration.

“These stories of community never take place in silos,” Girn said. “If you’re living in a place like Chinatown and you have Indigenous, Black, Chinese, South Asians all living close to each other, you’re bound to interact, you’re bound to build connections.”

He warned against overly romanticizing these connections, recognizing there were tensions, but highlights there was also friendship and connection. Looking at the histories of these communities, he said, might give us an “alternative idea of what Vancouver and British Columbia could be.” He goes on to discuss how that stands in direct opposition to the aim of government officials to make BC “white man’s country.”

Being in these close communities, Girn talked about the relationships that formed through marriage and religion. He gave the example of a marriage between Samuel Jagat Singh, an early convert to Christianity, and Alma Mae Stoner, a Black woman from St. Louis.

He also explained, in Sikh gurdwaras, “you lay a blanket over the holy book,” and in one of the photos of the Vancouver gurdwara, “this blanket has dragons on it.” Dragons don’t exist in South Asian mythology so the blanket could have come from Singapore, Japan, or Chinatown. Girn said this shows how they were “connecting and using the materials and the community that was at hand to make services unique.”

“Imperialism is a two way street”

The series thoroughly refutes the idea BC was ever a white province, despite the attempt of white settlers to make it such. With the caveat that others have made this point before him, Girn said, “Imperialism is a two-way street.

“You can’t just go to a country and not expect that country to come to you in many different ways, whether it’s through culture, through language, through food, through people.”

India was part of the British Empire until 1947 (Sri Lanka until 1948 if anyone is curious) and, as subjects of the Empire, there was a lot of tension surrounding identity. Their position should have meant the same equalities as white members of the Empire but racism prevented that from being the case. The response from some meant working harder to be recognized by the British Empire and for others, it meant distancing themselves and fighting for autonomy. Indians, like any other group of people, are not a monolith and their actions demonstrated that.

“There’s a lot of negotiation taking place in terms of how people want to situate themselves in proximity to power,” Girn said.

Some supported England in the war in 1914 and some on the Komagata Maru wore their regimental turbans to “show that affinity to England.” Other Sikhs, when asked to participate in a welcome procession for English royalty, “actually burned their medals and burned their uniforms and burned their certificates, just to show that protest and how they felt they’re being treated unjustly.

“There was a freedom movement based in North America [with] a strong chapter in Vancouver,” Girn explained. It was “heavily influenced by things like the French Revolution and American republicanism, and believed in the violent overthrow of the British.” He added they were “heavily influenced by Marxism and communism.”

Girn stressed this history is complicated.

“Small little vignettes”

This episode, and the series as a whole, provide “small little vignettes” that help viewers glimpse the real history of BC. As Girn put it, “No one can learn from history, no one can see the patterns that emerged, who actually isn’t honest enough and brave enough to tell the story in the first place. I think that’s what this documentary does.”

By focusing on the stories of marginalized communities, Girn said the documentary offers a “space for those voices to be heard.”

Telling untold histories

This episode provides not just a look into the South Asian community of BC, but also other marginalized communities. Though I knew most of the history covered in this episode, I still learned new details and this goes doubly for the previous episodes.

The episode does fall prey to treating communities as silos, with Girn one of the only speakers acknowledging the interrelated nature of communities. Another missed opportunity of the episode is to reckon (even in a small way) with the tension of being an immigrant from a marginalized community, while also understanding reconciliation is a responsibility of our presence here.

Of course, there’s only so much this documentary can do given its vast expanse so I don’t fault it too much, but hopefully it’ll open the doors for these stories to be told in greater depth and nuance.

This entire series provides a taste of the history in an accessible and engaging way and will hopefully urge viewers to dig deeper and learn more. At the very least, it will challenge assumptions that BC has not been a diverse place from the beginning.

British Columbia: An Untold History is playing on the Knowledge Network on Tuesdays at 9 p.m. It is also available to stream for free on www.knowledge.ca