[dropcap]P[/dropcap]eople of African descent have lived on the West Coast for more than a century. The first large migration of the black community, from California, settled in BC in the mid-1800s, mostly in Victoria and Salt Spring Island. Another wave of immigrants came to Canada during the 20th century, mainly from the Caribbean and Africa.

Today, Metro Vancouver is home to a significant number of people of African ancestry, many of whom are entrepreneurs, teachers, police officers, students, activists, and journalists, among other professions. Despite their enormous contribution to social, political, and economic development in the city, Vancouver’s African community has experienced systemic social problems such as discrimination, geographic displacement, and poverty.

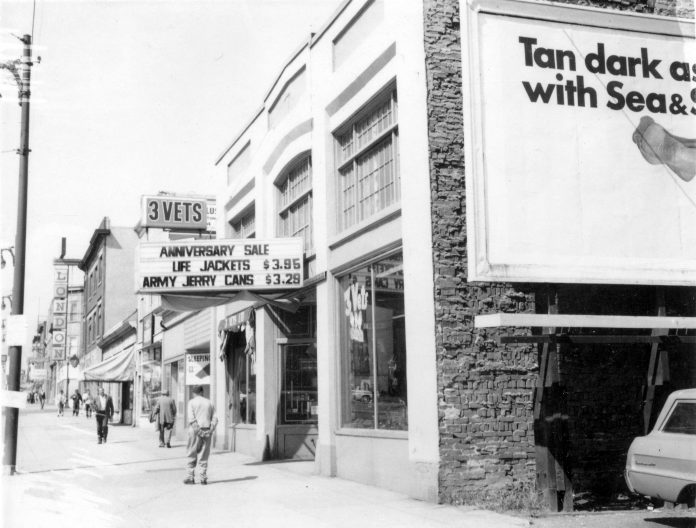

One of the most notable historic injustices committed against Vancouver’s African community was the destruction of the Hogan’s Alley community — a prominent Afro-Canadian neighbourhood in Vancouver, comprised of residences and businesses at the south-western side of Strathcona. Hogan’s Alley was demolished in the 1960s and early ‘70s in order to pave way for the construction of the Dunsmuir and Georgia viaducts — a decision that is still widely perceived to have been racially motivated.

Despite recent municipal acknowledgements, the Hogan’s Alley community hardly exists today. Sociologically speaking, the destruction of Hogan’s Alley created large displacement amongst Vancouver’s African community, thus dispersing what most resembled a cultural ‘hub’ at the time.

Metro Vancouver’s African community is one of the few communities that does not have an officially recognized neighbourhood or cultural centre.

Today, Metro Vancouver is known for its vibrant migrant communities: Chinatown, Japantown, Greektown, Little Italy on Commercial Drive, Surrey for South Asians, the Filipino community near Kingsway, the Iranian community in North Van — the list goes on, with the glaring exception of Afro-Canadians.

Metro Vancouver’s African community is one of the few communities that does not have either an officially recognized neighbourhood or cultural centre. As a result, Afro-Vancouverites feel marginalized and excluded by municipal governments.

The African community in the Greater Vancouver area deserves, first and foremost, an official apology from the City of Vancouver for the demolition of the Hogan’s Alley community and the eviction its residents. We also must see the restoration of the African community and the implementation of a cultural centre, where Afro-Vancouverites can congregate to celebrate their diversity and debate major issues affecting them.

More importantly, the creation of African spaces in Metro Vancouver would act as a node for integration of the African community. They would capacitate the African community to assemble and reflect on its social and economic status within Canadian society and Vancouver.

Spaces would also enable the community to gather and discuss some of the most pressing issues — such as discrimination, migration, multiculturalism, and resistance against police brutality through Black Lives Matter, which has inspired a chapter in Vancouver.

The recognition of Black History Month by the City of Vancouver in 2011, the annual Caribbean Days Festival, and Vancouver’s recent African Descent Festival also act as models for addressing the lack of spaces for the African community in Metro Vancouver.

Afro-Vancouverites have made tremendous contributions to this metropolitan city, and therefore we merit a postal code.