By: Eva Zhu

January 11 marked Sir John A. Macdonald Day, commemorating the country’s first Prime Minister. When you consider Macdonald’s appalling treatment of Indigenous people, his calendar holiday is a reminder of the colonialism at the root of Canadian society, which we can also see in our university’s namesake. Most of us probably don’t know Simon Fraser at all except as the guy our school is named after.

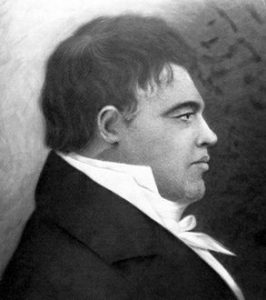

Simon Fraser II was born on May 20, 1776 in Mapletown, New York to Scottish immigrants Simon Fraser and Isabella Grant. Yes, he was given the same name as his father, because when you’re the tenth child, your parents have long run out of names. His father was a Loyalist and remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolutionary War, fighting in the Battle of Bennington. Unfortunately, he was captured by Patriot forces and died in an Albany war prison, after which his family moved to Cornwall.

In 1792, at sixteen years old, Simon Fraser started working as an apprentice at the North West Company. At the time, fur-trading was a prominent part of Montreal’s commercial scene. His mother had brothers who also worked in the fur trading business and their family was overall well connected. In short, Fraser was made for a career in the fur trade.

Fraser disappeared off the face of the earth for about 10 years during which almost nothing is known about him. He resurfaced in 1801 as one of the youngest trading partners in the North West Company. In 1805, he was tasked with expanding business outside of Montreal to the Rockies. During his years of adventure and exploration, Fraser wrote detailed journals and letters, which are publicly accessible (including through the SFU library).

According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, during this time Fraser “discovered” a vast patch of “wilderness domain” which he named New Caledonia, and settled in. Historical websites, including The Dictionary of Canadian Biography, praise Fraser as the “pioneer of permanent residence in mainland British Columbia.” True; Fraser did set up four forts, including the first white settlement west of the Rockies, Fort McLeod. However, Fort McLeod could only be built because the Sekani people, whose territory encompasses central and northeast British Columbia, were welcoming. They were also the first Indigenous nation to previously encounter Alexander Mackenzie and enable his exploration.

As with most of North America’s explorers, Fraser didn’t discover anything new, and he definitely wasn’t the first to build a permanent settlement. However, once again, history books remembered and forgave a European taking land that belonged to an Indigenous people by portraying him as a hero. We should take these accomplishments with a hefty grain of salt, and remember that the Indigenous peoples that lived in those areas had lived there for thousands of years prior.

Fraser’s most famous expedition was his “discovery” of the Fraser River. He wanted to find a new trade route to the Pacific, and followed the Fraser for 832 km thinking it was the Columbia River. When he got to its mouth in 1808, he realised that he was not equipped to brave the waters, that the river couldn’t be used for trade, that he had been completely wrong about sailing the Columbia . . . and he turned back, never completely traveling the river named after him. It was actually David Thompson who named the Fraser in his honour years later. Even more telling: both of these men were helped by Indigenous guides, whose people and ancestors had known the Lhta Koh or the Stó:lô (to name only a few traditional names) for centuries…

After that adventurous period in his life, Fraser returned to work for the North West Company, enduring aggressive and sometimes violent competition from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). He was one of the men arrested by Lord Selkirk (the head of the HBC) on grounds of treason, conspiracy, and accessory to murder for supposedly participating in the Battle of Seven Oaks (1816), which opposed settlers and the Métis nation. Fraser was tried but acquitted.

After his retirement in 1818, Fraser lived a pretty mundane life. The highlight of those years was his marriage to Catherine McDonnell in 1820. They settled near Cornwall, Ontario where they had nine children.

Simon Fraser died on August 18, 1862.

In 1965, a new university was built. To be fair, until 1963 this was going to be “Fraser University,” until someone realized the school would have been known (arguably more accurately) as “FU”. . . SFU had a better ring, and joined the ranks of universities named after colonial figures including McGill University (James McGill was a Montreal merchant and slave-owner), and Ryerson University (Egerton Ryerson was simultaneously a pioneer of public education in Ontario and a developer of the residential school system).

Yet as early as 1968, students actively protested against the university’s name, calling Fraser “a member of the vanguard of pirates, thieves, and carpetbaggers which dispossessed and usurped the [Indigenous people] of Canada from their rightful heritage.” They even offered a wildly controversial suggestion, “Louis Riel University,” which was shut down by the summer of that same year.

The trouble of naming an institution after an explorer is not news in itself. These issues peaked in 2017 as Canada celebrated 150 years of Confederation. One group of demonstrators installed a teepee on Parliament Hill to protest the Canada Day celebration. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau renamed the Langevin Block where his office is housed to cut ties with the architect of the residential school system and the Elementary Teacher’s Federation of Ontario made waves by voting to remove Sir John A. Macdonald’s name from elementary schools.

Yet here we are, with Sir John A. Macdonald Day marked on all Canadian calendars. Which is something to think about at SFU which, like many of Fraser’s settlements and “discoveries,” occupies the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Skxwú7mesh-ulh Úxwumixw, Stó:lo, and Tsleil-Waututh nations.