By: Kelly Chia, Peak Associate

Content warning: graphic descriptions of violence, sexual assault, racism

Soon Chung Park. Hyun Jung Grant. Sun Cha Kim. Yong Ae Yue. Delaina Ashley Yuan. Paul Andre Michels. Xiaojie “Emily” Tan. Daoyou Feng.

These are the eight names of the people that were killed in the mass shooting in Atlanta on March 17. Being a Chinese woman, this incident is perhaps the first time I felt both of those identities intersect — I could see myself, my mom, and my friends in these victims. Some of these victims were immigrant mothers, one of them would have been celebrating her 50th birthday. The stories of the victims and their families came out, and each one felt like a fresh personal wound.

While this crime was in Atlanta, vicious crimes against our elderly and our vulnerable are prevalent in Canada, and in Vancouver specifically. It follows a long list of attacks made across the Asian diaspora prior to and during the pandemic, and I’ve felt a myriad of anger, hurt, and helplessness. After all, how do you begin talking about feeling like a target?

A discussion with my peers about their personal experiences navigating these crimes has been a start. We talk about the presence and history of anti-Asian sentiment and how those factors play into anti-Asian hate today. I also include resources for people to learn more ways to support the Asian community.

I would also like to note that my article mainly focuses on East Asian, and specifically Chinese, perspectives because of my experiences and knowledge — but these crimes happen across the Asian diaspora.

Anti-Asian Sentiments in 2020 and 2021

In early January and February, social media and news outlets went wild with conspiracies about how COVID-19 had originated. Rumours suggesting that Chinese people eating bat soup in Wuhan caused the virus to spread began to circulate on social media. A quick search on Google for “coronavirus meme” easily reveals a plethora of memes and jokes in the same vein. These jokes increased anti-Asian sentiment by othering Chinese people and their cultural practices.

Daily Mail wrote an article spreading a video of someone consuming bat soup, describing her actions as “revolting” and suggesting a link between the soup and the virus. This language helped fan fears of Chinese people, even though it was later discovered that the person in the video was eating a dish in Palau four years prior, not in Wuhan.

Other rumours suggested that the virus was a bioweapon created in a lab in Wuhan, which aggravated fear and anger towards Chinese people. These videos and the ways they were framed have affected the perception of Chinese people, and people of East Asian descent. They not only framed Chinese people as the ones who originated COVID-19, but also suggested that they deserved it because of their eating habits and cultural practices. The rumours were unsubstantiated, but the damage had been done. A troubling correlation between East Asian people and the virus was forming: if you looked like you were Chinese, you were a carrier of the virus.

Former US president Donald Trump consistently referred to COVID-19 as “Kung-Flu” and “China virus,” nicknames that inflamed bigotry specifically toward Chinese people, but would also go on to affect East Asians, Southeast Asians, and anyone perceived as being Chinese.

Because of these actions to scapegoat Asians for the spread of COVID-19, our communities began to experience a spike in violent attacks and verbal abuse starting in March 2020. People started avoiding Chinese businesses because they associated the virus with Chinese people. Amy Go, president of the Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice (CCNCSJ) stated that many Chinese businesses and restaurants saw a drop in sales before the start of the pandemic.

Project 1907, a grassroots group of Asian women in Vancouver joined with the CCNCSJ, the Vancouver Asian Film Festival, and the Chinese Canadian National Council Toronto Chapter to release their findings on the data of anti-Asian racism in Canada.

They found that Canada had a higher number of anti-Asian racism reports per Asian capita than the United States. Additionally, of all sub-national regions in North America, BC had the most anti-Asian incidents reported per Asian capita. Verbal abuse made up about 65% of reported incidents, and assault made up about 30% of reported incidents.

The ties to COVID-19-related racism showed statistically, too. In a survey conducted by the CCNCSJ across 1,130 adults in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal, 14% of respondents were concerned that all Chinese or Asian people carried COVID-19. A further 20% thought that it was not safe to sit next to a Chinese or Asian person on a bus who is not wearing a mask.

At the time of writing, covidracism.ca has had 976 reported incidents of anti-Asian hate across Canada. The first incident that covidracism.ca reports is a Korean man being stabbed on March 17, 2020, in Montreal. The Korean community expressed concerns of rising anti-Asian sentiments, and the South Korean consulate issued a warning for Koreans in the city to be cautious.

In Vancouver, Global News reported a 92-year-old Asian man with dementia had racist remarks shouted at him before being shoved to the ground in East Vancouver on March 13, 2020. In the article, the police noted that, of the eleven crimes reported to them in March, five of them had an anti-Asian element.

In April, CTV reported that the Chinese Cultural Centre in Vancouver had hateful messages using slurs for Chinese people graffitied in the windows and walls. “Kill all,” one message read. “Let’s put a stop to [Chinese people] coming to Canada,” another message said. These two events marked the escalation of anti-Asian hate crimes in Vancouver.

While anti-Asian sentiments were sinophobic, it affected anyone that was perceived to be Asian. In May, Dakota Holmes, a young Indigenous woman was punched repeatedly in a Vancouver park after she sneezed. Holmes reported that the man called her racist slurs and told her to “go back to Asia,” before punching her. Following this, in November, two East Asian women were assaulted in two days: one whom was punched in the nose, and another was spat on by a man.

The constable on these cases expressed concern that in both cases, the victim and suspect had no relation to each other, suggesting a racial component to the attacks.

We then see the sharp increase in anti-Asian hate crimes reflected in the annual review done by the Vancouver Police Department, where anti-Asian hate crime incidents rose by 717% from 2019 to 2020, growing from 12 reports in the year prior to 98.

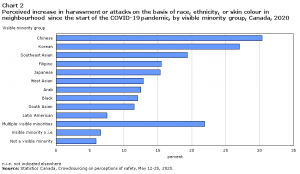

The effects of living through increased Asian hate crimes are palpable — fears of increased attacks and harassment have been felt throughout the Asian diaspora. In a survey conducted between May 12 to May 25, 2020, Statistics Canada reported that visible minorities (18% of participants) perceived an increase in harassment or attacks based on race, skin colour, or ethnicity since the start of the pandemic, with Asian people showing the most pronounced increase: Chinese people showed a 30% increase, Korean people at 27%, and Southeast Asians at 19%.

Reading about these attacks has a profound impact on my sense of personal safety. I discuss my experiences with three other individuals: Hilary Tsui, a student at SFU, Xenia Xu, a Master’s student living in the United States, and Alex Cagaoan, a SFU alumni.

Taking a closer look at our anti-Asian experiences

Late March last year, I stepped out of my house wearing a surgical mask for the first time. I remember taking it off before getting on the bus, worried that I’d draw too much attention to myself. I sat on the bus scrolling through Twitter feeds that made jests out of the “China Virus,” and Instagram stories of my friends saying that they were glared at for coughing. It marked the first time that I felt nervous to be in my own skin, which I had always felt relatively safe in despite the microaggressions I experienced growing up.

Xu echoes this story. “I remember during the beginning of the pandemic when masks were not mandatory in America — it was probably a few days after ‘lockdown’ — I wore a mask to the grocery shop,” Xu says.

Xu got a lot of weird looks from people, and like me, decided not to wear a mask and instead risk exposure to the virus because she was scared that she might be in danger.

While this was the first time I felt nervous about my safety, I knew that this wasn’t just about the virus. Everyone that I spoke to thought COVID-19 provided the fuel for the targeted attacks against Asians, but there was always potential for us to become targets because we had been targets before.

“Anti-Asian hate has always been in North America, since the times of the California gold rush, the 1914 Komagata Maru ship incident, and the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act in Canada,” Tsui says. “It was always there; it’s just that now the pandemic gave [people] a chance or excuse to act on that hate.”

A brief look at North American history proves that anti-Asian sentiment has spiked before — for example, in 1923, when the Federal Exclusion Act was put in place in BC to prevent Chinese people from entering Canada. We can also point to World War II, when Japanese citizens were kept in internment camps after Pearl Harbor, or the Vietnam war when people that had Asian features experienced perils of “looking like the enemy,” and Post-9/11, when vitriol against South Asians spiked.

The exploitation of Asian people despite fears of them is woven into the fabric of BC. Before BC became a province, Chinese labour was hired to build the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) because it was cheaper. They were paid $1 a day compared to their white workers at $1.50 to $2.50 a day. They also had the most dangerous tasks, like handing explosive nitroglycerin. Hundreds of Chinese Canadians died from malnutrition or accidents.

The celebratory photograph of the CPR completion does not show a single Chinese Canadian worker, despite their efforts. The government and white citizens wanted to celebrate a white BC, even though Chinese people were crucial to building. Once exploiting their labour became less profitable, BC passed laws to curb Chinese migration.

A few years later in 1885, the BC government would pass the Chinese head tax under the Chinese immigration act so that Chinese people needed to pay to enter Canada. This act devastated many of the migrants, most of whom were men hoping to bring their wives and children to Canada. It was a clear attempt to control the flow of Chinese migrants in the country, and by making sure they were being paid paltry wages, the government was also controlling their lives.

Today, we still notice the ways Asians become threats in news headlines. Prior to COVID-19, headlines of rich Chinese people buying real estate in the last 20 years prompted fears of an “Asian invasion” from some politicians.

News media has definitely contributed to anti-Chinese sentiment over the years, and readers make negative correlations between the actions of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chinese people, just as they have the correlation between COVID-19 and Chinese people. As the protests in Vancouver in solidarity with Hong Kong suggest, not all Chinese people support the actions of the CCP.

Anti-Asian sentiment moves in phases, and we know that COVID-19 is not the first or the last time it will happen. Prior to the pandemic, Cagaoan recalls a particularly harrowing experience in her neighbourhood of predominantly white people, making her nervous when anti-Asian hatred grew in the pandemic.

She tells me one of her neighbours had put up “no parking” signs on their lawns, noting that they didn’t want people parking on the street in front of their house even though it was public property. “It just made it clear to me and my family that the families in those homes are not pleased with having new neighbours to share street parking with,” she says.

“A few months after we moved in, a second-generation Indian family moved next door to us. They were the only South Asian family in our immediate area,” Cagoan says. She explains that most of the families living there were East Asian, white, and her own family was the only Filipino family in the area.

“[The father of the family] told us about a time that one of the [home]owners . . . came up to them as he was entering his car to [tell them] to never park there again,” Cagaoan says. The neighbours also left profanity-filled letters on their car window telling their ‘brown ass to stop parking on the street and to go back where they came from.’ This family would eventually end up moving in February 2021 after the constant harassment.

Again, this is not the first time that anti-Asian sentiments have been in North America, and as an immigrant, I have grown up with my fair shares of microaggressions. But the mass shooting in Atlanta feels like the first time we are truly speaking about it as a mainstream issue.

Xu believes that it is a cultural thing for Asians to be silent when things happen to us, to not cause any trouble or conflicts. My mom told me something similar: she didn’t want me to speak up because it was safer to be silent.

I think the perceived safety of silence is caused by the model minority myth: it portrays Asians as economically successful, clever, law-abiding citizens. The idea was that if we kept quietly to ourselves and worked, we would be safe and we would succeed.

This myth, of course, is not for our benefit, but to protect white supremacy while also using Asians to target other minorities. Kat Chow of NPR says the goal of this myth was to minimize the role of racism in the struggles of other ethnic groups, particularly Black Americans, because Asians were seemingly able to attain success. Being quiet only serves to hurt us and other minority groups by taking away our platform to speak on the injustices that we faced.

The model minority myth also undermines our own struggles, hiding them under the guise of the “successful Asian.” And because wildly successful Asians are portrayed in the media, it further entrenches this notion that all Asians are successful.

In an op-ed on the gaslighting of Asian-American struggles, Leanna Chan writes, “The struggle of being an Asian immigrant is a common experience, but it’s not one that we get to see on the screen . . . Crazy Rich Asians was an amazing milestone as it was the first film with an entirely Asian cast in 25 years . . . however, the film focused on the story of the rich and the elite. Some who watched the film may think every Asian person lives such an extravagant lifestyle. However, Asians have the largest income inequality of any racial group in the United States.”

“Politicians do not, and will not care about our community, even with us speaking up,” Xu says honestly. “I think it is quite obvious as anti-Asian crimes have been going on for a while. There were so many attacks, yet, barely any politicians spoke up . . . Literally, it felt like no one cared until the shooting in Atlanta. How many more lives does the Asian American community need to lose before our existence is recognized?

“It just feels really helpless.”

Then, there was the fear that came with being an Asian woman specifically. The culprit and authorities initially claimed it as a crime of sex addiction. The culprit’s assumption that these spas, owned by Xiaojie Tan, provided sex services shows that Asian women in massage parlors are conflated with being sex workers whether they provide those services or not — which is separate from the fact that the rights of sex workers are also important.

The hypersexualization of Asian massage workers is evident in racist phrases like “Me love you long time!” or “Happy hour!” which both Cagaoan and I were familiar with growing up.

In “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence,” a paper written by Sunny Woan, Woan explains that exploiting Asian women is a tool of colonization. Military presence, particularly during World War II, the Philippine-American War, and the Vietnam War heavily affected it.

“The Philippine-American war raged on for more than a decade, murdering over 250,000 Filipinos. . . . More than half the country lay in waste from American-caused destruction. While occupying the islands, the American soldiers referred to the Filipinas as ‘little brown fucking machines powered by rice.’” Woan goes on to say that the military claimed access to women’s bodies as a “necessity” and a “spoil” of war.

Today, these horrific experiences manifest in Asian women being fetishized as submissive and weak. Asian people are also trafficked at disproportionate rates, with most victims subjected to sexual exploitation, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

“While contemporary media and the arts portray women generally as objects for consumption, they cast Asian women into the most inferior of all positions, below white women. Portrayals of the interrelationships between white American GIs (a man enlisted in the army) who go overseas, the Asian women they meet there, and the white American woman back home show this dynamic,” Woan says.

It made me really cautious in my dating life, especially when a white man was interested in me. But beyond the precautions and stereotypes that we have learned to live with, there was also the dynamic of Asian women disproportionately being targets in anti-Asian hate incidents.

Project 1907 reported that in BC, Asian women overwhelmingly accounted for nearly 70% of all reported incidents. Stop AAPI Hate also reports a similar number — across 3,800 reported incidents, 68% were reported by women. The perception that Asian women are submissive also seems to make them more likely targets. Racism and misogyny are compounding factors that make Asian women more likely as targets because they are perceived as more submissive.

“My feelings of fear have grown recently as I hear more and more hate crimes happening in my community along with the increase of young women being harassed, assaulted, and going missing,” Cagaoan says.

Cagaoan is referring to the news and videos of women being followed and missing women in Vancouver. It’s something that I feel now whenever I go out, and the shooting in Atlanta has only worsened my fears of walking around as a Chinese woman and being targeted for it.

After all, if people are still arguing over whether there is a racial component in this crime, there is so much that they do not know about the ways in which Asians have been treated as enemies whenever white supremacy sees fit to make us enemies. How do you begin having a conversation about your struggles when so much of its history and its ongoing effects have seemingly been shoved under the proverbial rug?

The truth is, even as I am writing this, I find it troubling that we are our own advocates. I don’t mean that people of colour and allies haven’t been supportive, as I’ve found the most solidarity and assurance from fellow minority groups. I mean that it feels like we are having this really heavy conversation for the first time, and like we are having to justify why we are hurt. I am not confident that these conversations will amount to much more than pointing to the mass shooting in Atlanta as a tragic anomaly, even though there are plenty of assaults in America and in Canada to justify our fear of doing normal things like going out to get groceries.

“No one really even cared about us in America,” says Xu. “They never even bothered to learn about us. Most people just assume you are Chinese . . . when they see that you have Asian features such as black hair, dark brown eyes, brown-yellow skin.” And further, people commodify us by our food, our music, our entertainment to empathize with us.

Social media lit up March 17 in support of the victims of the shooting in Atlanta, but there were plenty of tweets like, “If you like anime, or Kpop, or Asian food, you should care about these issues.” While I appreciated the sentiment, I was hurt that Asians still needed to be measured by what we could culturally provide for people to simply empathize with us.

Tsui stresses that education is key, and I tend to agree. “I think it will take a lot of years, a lot of healing, and good leadership condemning racism, for [us to recover],” Tsui says.

I can’t stress anything more than continuing to listen to all people across the Asian diaspora about their experiences and to protect them. Asian hate is not a new trend — it is evidence of the ways white supremacy historically turns Asians into enemies in their narratives, just as quickly as they use Asians as model minorities to hurt other minority groups, deflecting the effects of systemic racism.

Please listen to us. Protect our elderly, our sex workers, our vulnerable. Please.

Soon Chung Park. Hyun Jung Grant. Sun Cha Kim. Yong Ae Yue. Delaina Ashley Yuan. Paul Andre Michels. Xiaojie “Emily” Tan. Daoyou Feng.

These were their names. May they rest in peace.

The web version of the article on www.the-peak.ca will include a section at the end with resources, organizations, and people to help support.

Resources

Fundraisers towards the Atlanta shooting victims

Eun Ja Kang, a survivor of the Atlanta shooting.

Elcias Hernadez Ortiz, a survivor of the Atlanta shooting who is currently undergoing trachea surgery.

Hyun Jung Kim, a victim of the Atlanta shooting, leaves two brothers behind. They will need help with basic living necessities, such as food, bills, and other expenses.

Delain Ashley Yaun, a victim of the Atlanta shooting, leaves two children behind. This funding goes towards their trust funds, and to cover her funeral expenses.

Paul Michels, a victim of the Atlanta shooting, this fund is being raised for Bonnie, Michels’ wife, to help with funeral proceedings with her husband.

Sun Cha Kim, a victim of the Atlanta shooting, this fund is raised on the family’s behalf to help provide a memorial and funeral for her.

Yong Ae Yue, a victim of the Atlanta shooting, this fund is raised for managing Yue’s affairs, costs for her family to travel to her memorial, and memorial service costs.

Ying Tan “Jami” Webb, the daughter of Xiaojie “Emily” Tan, this fund is raised to go to Jami to help her recover for trauma, settling her mother’s affairs, and potential legal fees since this is part of a murder investigation.

Gwangho Lee, the husband of Soon Chung Park, this fund is raised for Lee’s living expenses as he is unable to work due to the trauma of losing his wife.

Organizations to support

Project 1907, a grassroots group of Asian women that aims to explore Asian history, identity, and advocating for solidarity. They track incidents of anti-Asian racism, and have resources on solidarity, decolonization, anti-Asian racism.

SWAN Vancouver, a group that advocates and supports immigrant women engaged in indoor sex work. They help provide individual supports, like providing information and referrals to housing, immigration, and social services, as well as crisis management, advocacy in appointments. They also provide a platform where immigrant women engaged in sex work can disclose unsafe experiences of violence or injustice to help other women feel safer.

Yarrow Society, a foundation that supports low-income immigrant seniors in the Downtown Eastside and Chinatown. They provide seniors resources like groceries, accompanying them to their medical appointment to help them translate, and helping seniors apply for social housing.

CovidRacism, a website that tracks and reports anti-Asian racism across Canada.

Vancouver Chinatown Foundation hopes to protect historic buildings in Chinatown. One of their projects is to build more financially accessible housing on Hastings with 230 new homes, with a 50,000 square foot health center that serves the community.