By: Kelly Chia, Peak Associate

On June 19, CBC published an article investigating allegations of a “game” being played in the emergency room where health officials would guess the blood alcohol level of Indigenous patients. While these are allegations, they point to a deeper problem of discrimination in health care. This is far from the first instance where Indigenous peoples have been treated differently because of racial prejudice, and it makes sense that many Indigenous peoples report that they aren’t surprised by this game.

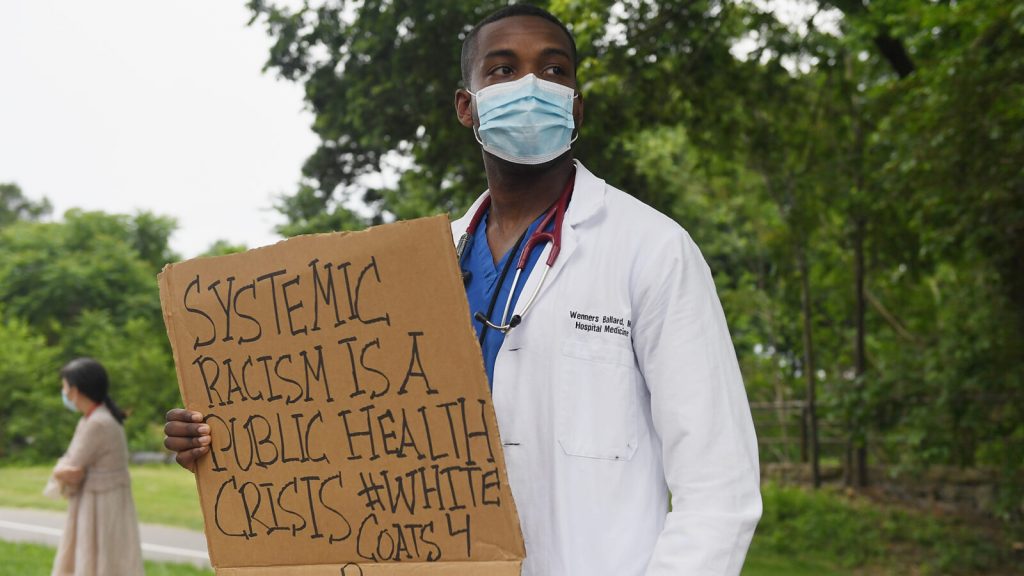

The racism in health care that affects Black and Indigenous peoples (BIPOC) is a systemic problem, not just the individual actions of racist health professionals that they may encounter. As currently constructed, the health care system for BIPOC is not built to serve their needs.

The primary objective of this article is to break down what factors prevent BIPOC from accessing health care compared to the rest of the Canadian population. This article is divided into the history and circumstances that have created systemic barriers for BIPOC, and how these circumstances now lead to BIPOC facing racial prejudice when they need medical help. A final section will be dedicated to educational resources to learn more about this topic, and organizations that alleviate BIPOC health barriers in BC by giving financial support to mental health organizations and vulnerable communities.

As a disclaimer, I am writing this as a Chinese immigrant and I recognize that my voice may not be the most appropriate one to frame these issues. I don’t claim to be an expert on this topic because I have not been affected by it like BIPOC have. However, I also feel that it is important that I use my privilege and platform to do the work in discussing structural racism that hurt BIPOC, which doesn’t just exist in criminal justice, but in institutions like health care.

I would also like to point to Idara L. Udonya, who wrote an excellent article for The Peak on medical racism. Udonya criticizes health experts for suggesting that Africa can be used for COVID-19 vaccine testing. Udonya explains how this suggestion is rooted in a history of Black bodies being used for medical experimentation. In Udonya’s words, “Black people are as deserving of care as any other race — medical ethics need not be applied to only white bodies. Black health matters; it always has, and it always should.”

Contextualizing medical racism as a structural problem

The racism that is being discussed in this article is not just interpersonal, but systemic: this means that it is not exclusive to BIPOC experiencing discrimination in their daily lives within the health care system. Systemic racism in health care is how legacies of colonial trauma continue to affect BIPOC because they experience socioeconomic barriers, better known as social determinants, to accessing health care.

The Indigenous Health Working Group of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada put together a fact sheet giving examples of barriers that create and maintain structural racism towards Indigenous peoples in Canada. One key barrier is Canada’s colonial policies. The effects of residential schools, outlawing Indigenous gatherings, and displacing communities have created intergenerational trauma that affects Indigenous mental health and culture.

Statistics Canada notes that Indigenous peoples have problems with accessing health care facilities as they live in remote areas. For example, most of the Inuit people (73%) live in Inuit Nunangat, where many of the communities are only accessible by air. As a result, 82% of the Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat report that they don’t have a family doctor. Even for Indigenous peoples living closer to or within populations, Statistics Canada reports that nearly one in five Indigenous peoples living off reserve and 16% of Métis people do not have a family doctor.

In the same report, Statistics Canada notes that as many as 18.3% in 2016 of the Indigenous population lived in “unsuitable” housing, which refers to the house not having enough rooms for the size of the household. According to the report, the low-quality housing leads the peoples of Inuit Nunangat to experience poor respiratory health and overcrowding, which lead to higher rates of tuberculosis (TB) infection compared to the rest of the Canadian population.

Statistics Canada also found that high levels of the Indigenous population have pre-existing health conditions: 36% of Indigenous peoples 50 and older that live off reserve have high blood pressure, and 20% of them report having diabetes. Comparatively, 33% of all Canadians that are 50 and older have high blood pressure and 14% report having diabetes.

Brenda L. Gunn, an associate professor at the University of Manitoba, writes on how factors like these cause Indigenous health and welfare to fall behind compared to the rest of the Canadian population: “In Manitoba, the infant mortality rate for [Indigenous peoples] is almost double that of [non-Indigenous peoples]. At the other end of the spectrum of life, the mean life expectancy for [Indigenous] men is projected to be 70.3 years compared to 79 years for other Canadian men. Life expectancy for [Indigenous] women is predicted to be 77 years compared to 83 years for other Canadian women.”

These are social determinants that have strong, long-term impacts on Indigenous peoples, and similar ones exist to enforce health inequities for Black people in Canada. Black Health Alliance (BHA), a community-led charity that works to improve Black health in Canada, finds that Black Canadians are overrepresented in the Canadian prison population (9.4%), while representing only 2.5% of the Canadian population.

BHA also finds that 24% of Black Ontarians are “low income,” compared to 14.4% of the general Ontario population. 18% of Black Canadians live in poverty, though they make up less than 3% of the population. These social determinants have a direct impact on the chronic illnesses that Black people inherit. BHA states that while diseases like sickle cell disease may be inherited at greater rates in some ethnicities, many chronic illnesses are a result of not having strong access to education, support networks, and stress.

A distinctive lack of race-specific research data in health care can also lead to misdiagnosing fatal illnesses, or missing symptoms that are race-specific. In a paper published in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Undeserved, researchers Onye Nnorom, Nicole Findlay, Nakia K Lee-Foon, Ankur A Jain, Carolyn P Ziegler, Fran E Scott, Patricia Rodney, and Aisha K Lofters write that Black Canadian women are under-screened for breast and cervical cancer, despite evidence from the United States suggesting that Black women may be predisposed to increased risks or worse outcomes from these diseases.

While I used statistics for Black and Indigenous peoples here, I would like to stress that my intention is to compare how they fare in accessing health care compared to the rest of the Canadian population, not to pit them against each other. Racism is embedded in multiple institutions, including denying equal health care to BIPOC. In order to fully alleviate the playing field in the health and welfare of BIPOC, we must first look at how to take care of these social determinants.

How structural racism manifests today

The effects of these social determinants trickle down into more than just an issue of individuals in health care, although that does contribute to the general tension between BIPOC and the medical system.

In this next section, I have asked BIPOC from the SFU community to give their input on their experiences with inadequate health care. Two people responded, one of which chose to remain anonymous. The commonality in both of their responses is that they feel they were either ignored or had their symptoms dismissed.

In 2016, Amelia Boissoneau, an SFU student, was sick with what she knew wasn’t a normal flu. She went to a clinic to get it checked out, and saw that it was completely empty. “I approached the receptionist and handed her my ID [ . . . ] one was my status card. I was in pretty rough shape, and asked to be squeezed in to see the doctor.” Boissoneau was promptly dismissed at the receptionist desk, and told that she would recover in a few days. “I knew I had more than the flu. I tried to explain to her how I knew it was not just a flu. But she refused to listen to me and sent me off.”

Days later, an intense pain started to develop from her ear canal into her jaw. Boissoneau cited this as some of the worst pain that she had ever felt. “I ended up developing a horrible ear infection that was so painful it had me bedridden. My hearing was so sensitive [that] any sound hurt my ears. This all happened because the receptionist wouldn’t let me see the doctor when I knew they had no patients at the moment.”

Boissoneau’s story echoes what many Indigenous peoples experience when they seek health care — they are ignored. The report maintains that racism is prevalent from 39 to 78% in multiple Indigenous survey studies across geographic settings in health care. Indigenous peoples also have to be wary about the racist assumptions of their health care providers. This may lead to them not seeking medical help until it is urgent because of their distrust in health care.

In an article investigating Indigenous access to health care, Moira Wyton writes that because Indigenous peoples may not seek health care until it is urgent, they are often redirected to emergency rooms. Emergency rooms are not equipped to handle chronic illness because it’s not a one-time fix, nor are they necessarily aware of how to properly handle the cultural weight of treating them.

Although Indigenous peoples in BC drink at much lower levels compared to non-Indigenous Canadians, one of the first questions that an Indigenous person may be asked at the emergency room is how much they had to drink. This question comes from what Gunn describes as the harmful stereotype of the “drunken Indian,” referring to Indigenous peoples being prone to substance abuse. Of course, the stereotype itself is connected to European fur traders introducing liquor to Indigenous communities. Because health care providers may hold the assumption that Indigenous patients have an alcohol or substance addiction, they may ignore symptoms and assume that is the cause of the medical issues they may have.

This lack of urgency in treating BIPOC patients is dangerous. In regards to Black patients, in a 2016 study conducted amongst medical students, roughly 50% had false beliefs about how Black people experience pain. Contributing to failing Black patients in pain, another study finds that Black patients were 22% less likely than White patients to receive medication.

Additionally, the CDC found that in the United States, Black women were 4 to 5 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes compared to White women. An anonymous student wrote that in their experience, people in health care did not believe the pain of Black people, leading to delayed treatment, or worse, none whatsoever..

“Anti-Black racism in medicine has [gotten] to the point where if a doctor refuses to treat my friends, they ask for the doctor to note refusal to treat them in their medical record. Then [suddenly,] the doctor backtracks, changes their mind, and decides to treat them because they fear consequences. It’s sad that doctors are more afraid of being perceived as racist than actually perpetuating racism.”

Not having enough BIPOC represented in health care is also what leads to doctors not understanding how systemic racism affects BIPOC. This is especially prevalent in mental care. “As a Black and Muslim student, I find counselling services at SFU inaccessible because of the lack of cultural competency to understand the context of my experiences and how I must navigate the world. I constantly have to go through the emotional and triggering burden of giving a “Racism 101” or “Islam 101 lesson” before even going into the medical reason I’m there, which is typically for mental health support, which is intertwined with facing anti-Black racism anyways,” the student writes.

“When SOCA was being evicted, and safe Black space was at threat of not existing on campus[,] I, as well as other students that rely on SOCA, faced heightened anxiety as Black students had to explain basics of structural racism while facing racist backlash. People failed courses or withdrew from semesters, all while SFU was complicit in the refusal to protect Black students. I speak from anecdotal experience and witnessing other’s experiences, but unfortunately there is not even race-based data to show what I’m talking about because SFU does not collect it, to the detriment of Black students.”

Not having race-based data is disadvantageous, especially during COVID-19. COVID-19 is striking BIPOC communities harder because they are more susceptible to chronic illness due to socioeconomic stressors. Dr. Eileen de Villa found that although Black people make up 9% of the Toronto city population, they made up 21%of reported cases.

They may also be more affected by the virus. In the 12 US States reporting race and ethnicity COVID data, Black residents are 2.5 times as likely to die from the virus compared to the rest of the population. While we are expecting and seeing the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on vulnerable BIPOC communities, we do not have race-based data to prove it yet.

Final remarks, and possible solutions

The question is, where do we go from here?

To increase the level of trust for BIPOC in health care, we do not just need more health care training in how to handle implicit bias and BIPOC issues, but also BIPOC in health care positions. They understand how systemic racism impacts their patients, and this will help in alleviating some of the inequalities in the medical system..

We also need to push for more ethnocultural data to better support BIPOC with chronic illnesses. In June, BC Human Rights Commissioner, Kasri Govender, joined human rights commissioners across Canada in calling for the collection of such data. More recently, she agreed to provide advice to the B.C. government about the human rights implications of disaggregated data collection and recommendations for action.

Simply put, we need to educate, fund, and uplift more BIPOC voices in health care. I have attached some resources here that you can learn about and support. While not all of these are strictly related to health care, they help alleviate the factors that affect healthcare distribution to BIPOC communities.

Black Therapy and Advocacy Fund, which have been working to connect licensed therapists in the Lower Mainland to recipients during their intake period. This fund was created in recognition of the need for Black therapy resources that are accessible to the Black community in Vancouver.

Black Health Alliance, which I referenced earlier as an organization that works to improve Black communities. They also provide resources for learning about Black social inequity in Canada. In 2018, they secured one million dollars towards Black Youth Mental Health with CAMH, TAIBU, Wellesley Institute, and East Metro Youth Services.

Black in BC Community Support Fund for COVID-19. They’ve been providing one-time, non-refundable $150 payments to Black people who reside mainly in Vancouver, but in BC, Canada, more broadly.

Black and Indigenous Care Fund, seeking to give funds for self care and body work to Black and Indigenous (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) peoples on the frontlines. To access or ask questions about these funds, please email blackandindigenouscarefund@gmail.com.

Compilation of Indigenous funding programs funded by the Crown-Indigenous Relations Canada (CIRNAC) and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC).

Indigenous Community Fund, which is funded by the Government of Canada at $380 million. It should support vulnerable community members, help alleviate food insecurity, provide mental health assistance, and educational support for children, and more. To find more information, contact regional officers.

Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health in Canada. This book is edited by Margo Greenwood, Sarah de Leeuw, Nicole Marie Lindsay, and Charlotte Reading about the health disparities that affect Indigenous people in Canada.

Medicine Unbundled: A Journey through the Minefields of Indigenous Health Care. This book is written by Gary Geddes, where Songhees elder Joan Morris first relates the story of her mother’s seventeen year institutionalization as well as her own experiences of racism in the health system. It also navigates other Indigenous elders’ experiences with contemporary Canadian medicine.

From Enforcers to Guardians. This book is written by Hannah L. F. Cooper, and Mindy Thompson Fullilove. It examines how the way police violence targets Black communities through a public health lens to see how far its suffering is extended to. Assessing

Differential Impacts of COVID-19 on Black Communities. Conducted by Gregoria A. Millett, Austin T. Jones, David Benkeser, and many other researchers, this study shows how COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black communities in the United States.

Google

Please visit the web sites we stick to, which includes this 1, as it represents our picks through the web.