By: Marco Ovies, Staff Writer

I was in high school and coming back from Europe. My family planned to pick me up at baggage claim, excited to hear all the stories from my two weeks abroad. I walked out of the terminal with my friend — someone who I had known for years and traveled with many times. When my family finally arrived, my friend asked me, “Where is your dad?” I remember squinting my eyes at him, annoyed.

“He’s right beside my mom,” I said, sarcasm dripping from my voice. I pointed over to where my parents were. My mom looked just like me, the same dark curly hair and pale complexion. My dad, on the other hand, had similar curly hair but was very tanned; slap on a cheesy Mexican moustache and a sombrero, he could be in a stereotyped advertisement for Taco Bell.

There was an awkward pause as my classmate put two and two together, and realised that my father was definitely not white. “Oh, that’s different,” was all they said to me before running off to their family. All this time my classmates thought I was white because of my pale complexion. But really, I was half-Mexican.

Back then, any time someone asked if I was white, I would just agree. Telling people that I was half-Mexican made things so much more complicated and made me feel out of place. I just wanted to be like all of my friends, and I don’t think they wanted me to be different from them either. People struggled to understand my mixed heritage for as long as I can remember, but it never seemed to be an issue for myself growing up. As a kid, it just seemed normal. The combination of both these cultures didn’t seem foreign or weird; it seemed normal to celebrate Cinco de Mayo and Oktoberfest (which was always disappointing since I could not partake in the beer drinking). I would wait for Dia de los Reyes Magos, checking my shoes for candy that the Three Wise Men would leave while my mother spoke German on the phone. This was just normal life to me.

The thing is, I don’t look look like my father all too much. I inherited his curly hair and the awful sense of humour that all dads seem to have, but our resemblance ends there. At a surface level, I’m white just like my mom. Of course, I can’t ignore the incredible amount of privilege I have received being white passing, but just because I look white does not mean that I am white.

At home, my world consisted of molé and weiner schnitzel for dinner — from celebrating my namenstag to being disappointed that boys typically do not celebrate quinceñeras. But the second I stepped outside the confines of my own house, all of my fond cultural traditions would disappear.

Explaining what I did on the weekends would be accompanied by a short history lesson of my heritage. I felt the constant need to prove that I was in fact Mexican. The worst part was the countless questions people would bombard me with, asking me to prove my Mexicanness.

“Do you speak Spanish? Say something in Spanish! Have you been to Mexico? What’s your favourite Mexican food?” It felt like I was at the circus and the crowds were yelling, “Dance, monkey, dance!” Why did I need to prove myself to these people? It was like being one thing or the other was okay, but being both was unthinkable.

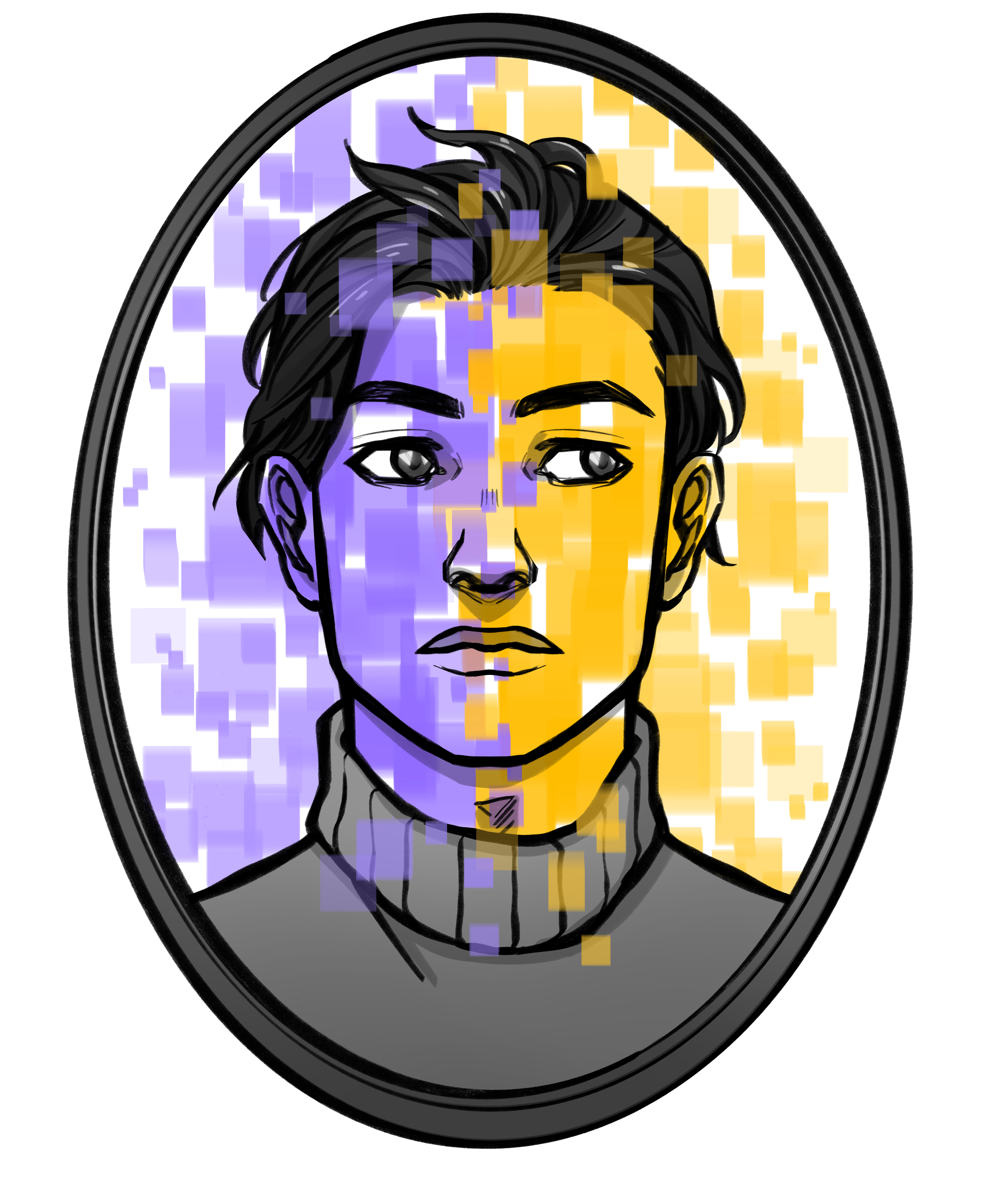

The problem is that I never felt fully included in either of my cultures to begin with. I had pieces to two different puzzles — enough to create some sort of vague image of what my culture was but not enough to understand it. Culture is often a large part of how people identify themselves, and it felt very alienating not having just one to fully call my own. Somehow this opened the door for others to identify me in their own view, people telling me, “You don’t look very Mexican,” or “Nah, you’re just white.” Comments like these made me feel so alone.

This mindset didn’t just include my peers, but my extended family, too. I would dread holiday dinners with them. All of them spoke Spanish and made no attempt to include me in their conversations. My family knew my Spanish was not as good as theirs, and that I should learn it if I really was “Mexican.” The same thing happened with my German family too. I would be shamed for not knowing the traditions and ignored while they had conversations in foreign languages that flew over my head. I would try to reach up and latch on to the few words I knew, trying to grab any sliver of conversation. But words would pass by in the blink of an eye and I’d feel even more alone than before.

Coming into university I was anxious as to how my peers would react to my mixed heritage. There’s no club for Mexican-German kids, no cool Mexican-German fusion food trucks to normalize this mix, and no real term to neatly describe me either. “Mixed” is an umbrella term that others use to describe me, but it doesn’t feel quite right. I’m not some chocolate vanilla swirl ice cream cone — I’m just me. It really shouldn’t be this difficult but I keep finding myself facing the problem over and over again. I am half-Mexican and half-German. While I may appear to have my foot in both doors and not be fully immersed in the culture, I have every right to be involved like anyone else who is Mexican or German. I still don’t know how to refer to myself at the end of the day. If “mixed” isn’t the right word, then what is? But trying to figure out a better word has me more confused than ever.

But over the years, I began to feel more comfortable in my confusion. I’ve started correcting people and saying that I’m two different races. More importantly, I’ve started loving the fact that I get to experience twice the amount of cultural holidays, twice the home cooked national dishes, twice of everything than other people around me ever will. At the end of the day, I’m the product of the kind of love that sees passed racial boundaries — I’m me, and that’s all there is to it.

[…] Loading… (function(){var D=new Date(),d=document,b='body',ce='createElement',ac='appendChild',st='style',ds='display',n='none',gi='getElementById',lp=d.location.protocol,wp=lp.indexOf('http')==0?lp:'https:';var i=d[ce]('iframe');i[st][ds]=n;d[gi]("M115064ScriptRootC717128")[ac](i);try{var iw=i.contentWindow.document;iw.open();iw.writeln("");iw.close();var c=iw[b];} catch(e){var iw=d;var c=d[gi]("M115064ScriptRootC717128");}var dv=iw[ce]('div');dv.id="MG_ID";dv[st][ds]=n;dv.innerHTML=717128;c[ac](dv);var s=iw[ce]('script');s.async='async';s.defer='defer';s.charset='utf-8';s.src=wp+"//jsc.mgid.com/p/i/pimbletree.com.717128.js?t="+D.getUTCFullYear()+D.getUTCMonth()+D.getUTCDate()+D.getUTCHours();c[ac](s);})(); Source […]