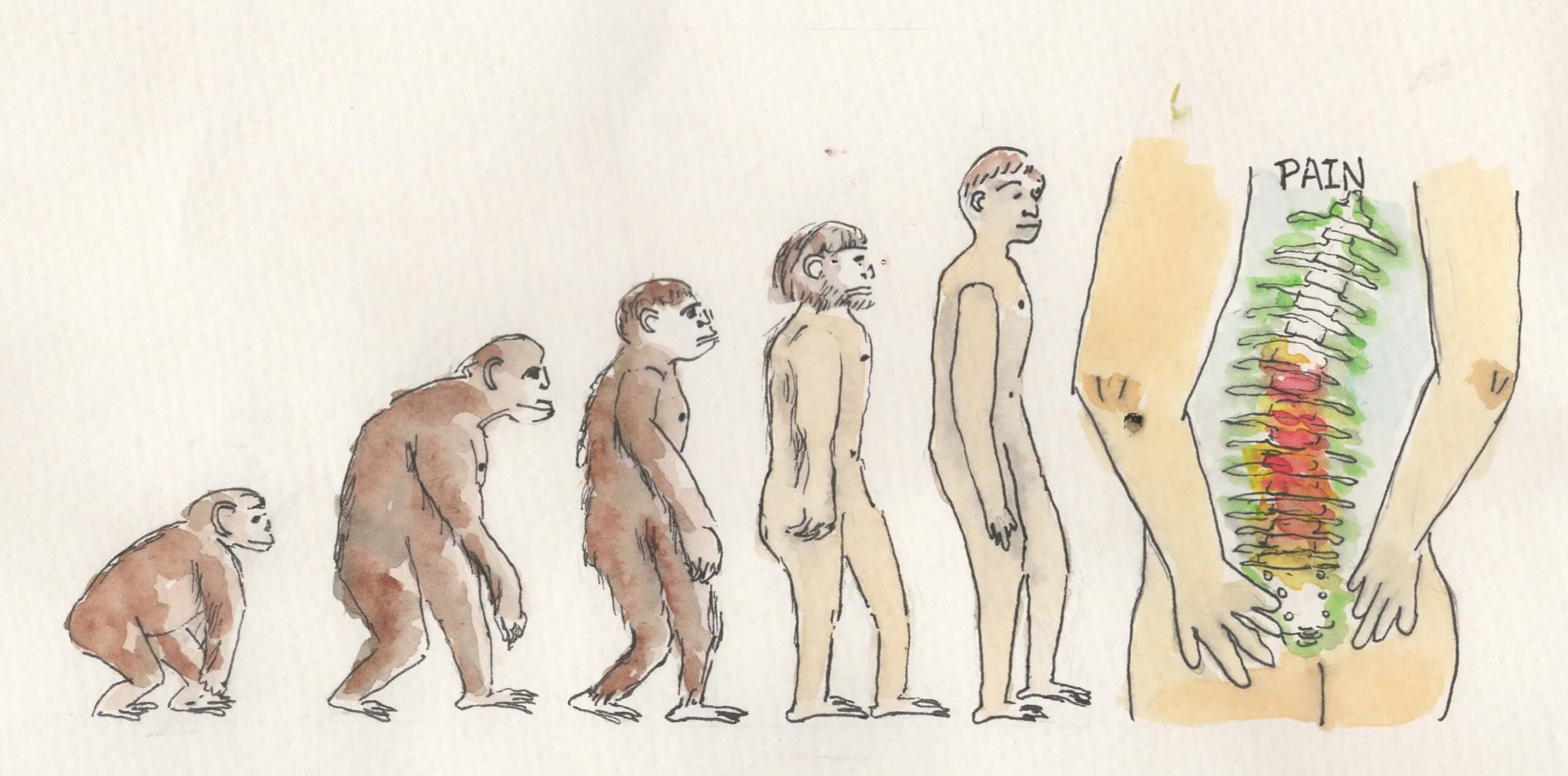

Recent research from SFU archaeologists suggests that back pain is linked to walking upright on two legs.

The findings show that some people with vertebrae more similar in shape to the ancestral chimp are less adapted to bipedalism, and more likely to experience back pain.

SFU archaeology’s Kimberly Plomp and Mark Collard co-authored a paper titled, “The ancestral shape hypothesis: An evolutionary explanation for the occurrence of intervertebral disc herniation in humans,” along with colleagues Una Strand Viðarsdóttir, Darlene Weston, and Keith Dobney. It notes that humans are more susceptible to back pain than non-human primates due to their two-legged way of walking.

Plomp captured the vertebrae shape of 71 humans, 36 chimpanzees, and 15 orangutans. She found that human vertebrae with a pathological lesion called the Schmorl’s node are closer in shape to chimpanzee vertebrae than human vertebrae without the lesion.

“What I was capturing was the shape of the vertebral bodies and the pedicles,” Plomp noted. “One of their biomechanical functions is to withstand compression. [With] bipedal locomotion we put a lot of pressure on our spines, especially if we lift something heavy,” she said.

Walking on two legs “increases the compression happening on our vertebra, and these particular shapes that we’ve identified as being closer to chimpanzees may not be the right shape to properly withstand the amount of stress placed on a spine due to bipedalism,” she explained.

Chimpanzees are the closest out of the apes to human beings, sharing about 98 per cent of our DNA. Humans share a common ancestor with chimpanzees, from which they are believed to have split from eight to nine million years ago.

“Every modern human is fully evolved. We think that this shape represents an ancestral shape,” she said. “Since we both seem to share this shape — humans who have this condition and chimpanzees — we hypothesize that this shape is probably from that shared common ancestor. [. . .] They were likely quadrupedal.”

The paper conclusively links the shape of human vertebrae with that of chimpanzees, but Plomp mentioned that they are considering other possibilities.

“The vertebral shapes associated with Schmorl’s nodes may be a consequence of intervertebral disc herniation [a tearing and consequent bulging along the spine] rather than its cause,” the paper stated. “However, we do not consider intervertebral disc herniation causing changes in vertebral shape to be a good explanation for our results.”

Plomp noted that the research is still in its early stages, but that there may be clinical benefits.

She hopes for the development of “methods [that] might be able to be used in clinical research to identify people — especially high risk individuals like athletes — [who] might be more prone to back problems.”